In the northern plains of India, fields and farms have united families for generations. However, changing climate conditions, along with social and economic challenges, have uprooted these communities from the soil and pushed them into cities where ways of living grow increasingly distant from what was once familiar, and families are dispersed into smaller units. Faced with this reality, Umesh S., a multidisciplinary artist, has dedicated his work to exploring indigenous farming methods. His practice spans sculpting bodies from dust and clay, collecting forgotten agrarian tools, and weaving rural dialects into his poetry and performances. Through painting and printmaking, he gives form and voice to the struggles of India’s farming communities. He is represented by Chemould CoLab.

The origin of our sacred rituals, like Chhat Puja, was connected to the sun and the river. We can still see the sun and the river, but we don’t revere them. Artificial ponds and man-made temples have replaced them.

Umesh S.

Multidisciplinary artist

Priyanka Singh Parihar How would you describe your childhood in relation to land and community?

Umesh S. As a child, I was close to the land, to the soil. I spent my days on to the farms and orchards, sometimes helping with farming work. I remember my family living together; we were a big joint family, and everyone farmed together. My mother was also deeply involved in farming, although she stayed at home. We used our home as a Khalihaan. My whole family would gather there, and my mother would harvest grains by beating the crops with a wooden stick (Mungdi). In the harvesting season, crops would fill the khlaihaan day after day.

We mostly used natural manure for the fields back then. I remember that all the household waste—cow dung, husk, leftover food—everything was collected in one place. It became a big pile, and when the season came, everyone would carry it on their heads to spread in the fields. In those days, chemical fertilisers and pesticides weren’t used much. The fields were very fertile then; the yield was very good. Everything was natural.

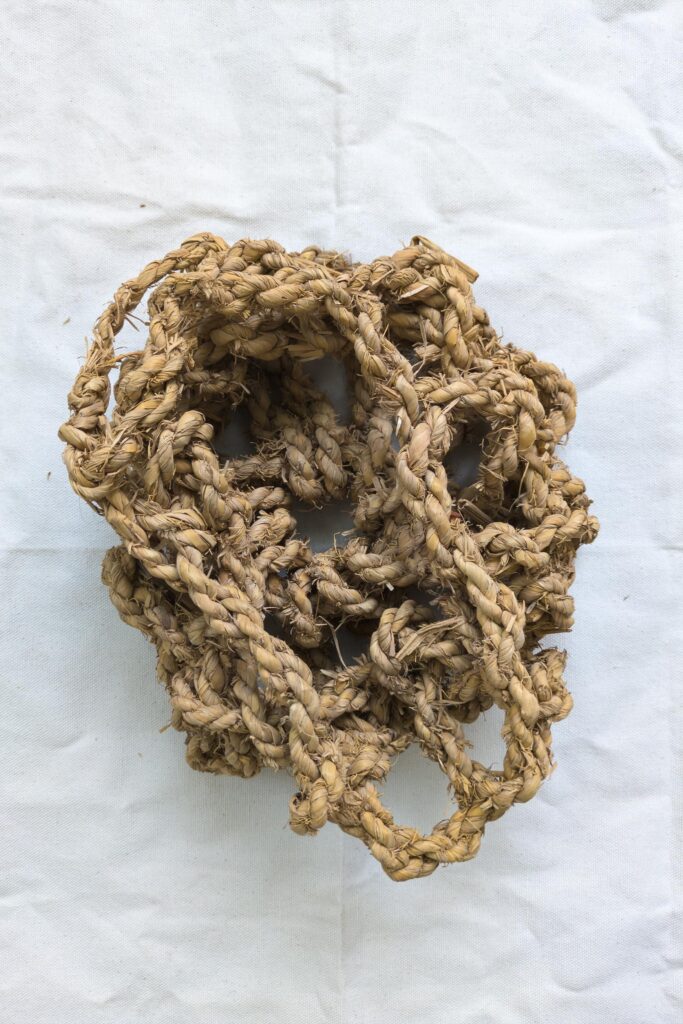

We used to do everything ourselves, making ropes from natural fibre.

Priyanka Singh Parihar Agriculture has been an ancestral practice in your family. What changes have you witnessed that connect your art to agricultural memory?

Umesh S. When I was at Banaras Hindu University, in my second and third year, I began thinking about my art practice. I thought about the struggles, social and economic, my family faced as farmers, not being able to meet the basic necessities and rights of health, and feeling constrained with medical bills and clothing. The changing climate was affecting our farming practices. Sometimes there were heavy rains, sometimes floods, sometimes droughts, and we couldn’t earn anything from it.

I remember when I came to the city and visited the mall. I saw the price of grains—chana being sold for ₹100 per kilogram, when we had sold it for ₹20. We were working so hard, and still our grains sold cheaply, and in the mall, they were overpriced. I felt provoked by the injustice and by the parasitic systems that kept us struggling.

Priyanka Singh Parihar The body comes from the land, yet today’s systems have made us forget this truth. How can we reclaim autonomy over our bodies and the land through food and farming?

Umesh S. Education and awareness are very important. We are forgetting the old ways. For example, we once ate in Pattal plates made from large, dried leaves; we were already living sustainably, but then plastic plates were introduced in markets and sold in villages. We also had wooden bridges made by villagers, people who could depend on themselves and not the government. These things have vanished, and it has destroyed our local culture.

Our bodies are also getting weaker. I remember my grandfather used to work the land all day, but now people don’t have that kind of strength. My father, a migrant farmer, moved between cities and villages for seasonal work. We stopped farming and migrated to the city. When he came to the village again during COVID and wanted to farm again, he couldn’t. He lost his strength and got tired often. The modern way of consumption and eating is also causing serious health issues, such as obesity and other diseases.

The indigenous knowledge was a blessing, and we have forgotten it. Every family in our village knew how to make rope beds. Today, they are being sold for ₹75000, but villagers can’t afford them or remember how to make them. This knowledge is eroding. The same is happening with terracotta homes, which were also a sustainable way of living that has vanished and been replaced by houses made of cement. These houses are dangerous during rising heatwaves Many people in the village can’t afford air conditioners or coolers, and people are dying. Ten people died in my village due to heat and dehydration. Terracotta homes kept us cool. We became influenced by urban lifestyle.

When I was at Banaras Hindu University, in my second and third year, I began thinking about my art practice. I thought about the struggles, social and economic, my family faced as farmers, not being able to meet the basic necessities and rights of health, and feeling constrained with medical bills and clothing. I felt provoked by the injustice and by the parasitic systems that kept us struggling.

Umesh S.

Multidisciplinary artist

I was at the farmers’ protest for ten days, at the Singhu border. It was a very important protest; it was unstoppable. Farmers came from everywhere—from UP, Bihar, and Orissa. There was no discrimination against social class, and everyone ate together. People served, cooked, and fed; they were united. It was a historic protest that overpowered the government.

Umesh S.

Multidisciplinary artist

Priyanka Singh Parihar Do you believe that preserving indigenous farming methods can help us build a more sustainable future?

Umesh S. The government must provide subsidies; at the grassroots level, it is difficult. I have spoken to farmers, especially the small farmers, and they believe they won’t be able to make a living with traditional farming methods, and they are scared of low yields. In villages, they are not incentivised for organic farming. Systemic change is needed, but the current farming subsidies are supporting industrial farming and capitalism.

Small farmers are leaving the farming practice. The new generation is not getting involved, which is scary, as this could lead to a food crisis. Power will rest solely in the hands of industrialists, and we will forget to work with the land.

Small farmers feel hopeless. We need hope and examples and stories of success that prove there is still a possibility.

Priyanka Singh Parihar What about the farmers’ protest (2020–2021)? How did it unite the farming community?

Umesh S. I was at the farmers’ protest for ten days, at the Singhu border. It was a very important protest; it was unstoppable. The farmers were hopeful and united against corporate farming. Under the proposed laws, corporatescould stock agricultural produce without limits, leading to market monopolisation. This possibility frightened farmers.

The protest had its own rhythm. Every day it began with bhajans (devotional songs); then, around 7 a.m. there were speeches, and from midday to 1 p.m. it had a great, furious energy of revolution, and by evening it ended again with bhajans.

Farmers came from everywhere—from UP, Bihar, and Orissa. There was no discrimination against social class, and everyone ate together. People served, cooked, and fed; they were united. It was a historic protest that overpowered the government.

Priyanka Singh Parihar In times of ecological crisis, what role can art and the artist play in helping us reimagine or challenge the status quo?

Umesh S. Stepping out of the studio and working on the ground. To be in a studio in a metropolitan city like Mumbai and paint a village in Bihar is not the right approach. You cannot witness the changes there, and your work loses its essence.

Many creatives are forming communities and collectives. I recieved a small grant to work near the Yamuna River with my friend, who is also an artist, Gyanvant Yadav, in Chilla village. Many farmers live there and now they are being moved because of yearly floods that destroy their homes. Thinking about this, we created a project to design a mobile home on vehicles. We don’t want to just take pictures and leave; we plan to create a long-term project, which will go on even after our grant period is over. We will visit this place and the people who live there. We want to create relations and trust with this community. We want to collaborate with the children and give them workshops to explore their environment by drawing rivers and farming practices and to translate their experiences into visuals. We met lots of teenagers who have left schooling, and we encourage them to study so they are confident and can have the capacity to support their household.

Priyanka Singh Parihar Are they still farming?

Umesh S. Yes, because their ancestors migrated from Bihar fifty years ago. They can make a living here because they sell the harvest immediately and get paid. This is different from village farming, where people work for months or even a full year, day and night, and only earn if the yield is good.

We want to support them to see societal change. It’s not about growing solely as an artist; if the artist’s project is growing in separation from society, then it becomes problematic, and we end up functioning like the systems we criticise. We have to work collectively with the village.

When I was a child, I saw many parents forbidding their children from speaking Bhojpuri, saying it was “bad”. Hearing my mother tongue being insulted affected me deeply, and I thought, I have to work with this theme. How can a native language be a bad thing?

Umesh S.

Multidisciplinary artist

Priyanka Singh Parihar If artists work for land, will it have a long-term impact on justice and government?

Umesh S. Yes, but big industries, like cinema, are working for the government. Art should be the mirror of society, but now it’s a mirror in name only The film industry often creates narratives that benefit the government. They aren’t working for the country. The same happens in the art world, and once an artist gains recognition, they often start working for the government. They create murals for the governmental project. But this shouldn’t happen; we have to criticise what isn’t working.

Priyanka Singh Parihar Poetry stirs the deepest parts of the human spirit. What inspires you to write and recite in your native tongue?

Umesh S. I’ve performed poetry, and I see how much it touches people. Poetry is powerful, even more so than other art forms. I did a performance at the Indian Art Fair, and I saw people crying. They were moved.

I also tried writing poetry every day in Siwan. When I recited them, people were deeply moved. When I returned after four or five months, they still remembered the poetry. I also wrote some songs with villagers, which they sang. They felt connected, especially because it was in Bhojpuri, their mother tongue.

Priyanka Singh Parihar Do you see your use of Hindi and Bhojpuri as a form of cultural resistance in postcolonial India?

Umesh S. I used to think that if my parents had put me in an English-medium school, I would have spoken good English, but studying in a regional dialect also has its own benefits. I know words from my grandmother’s generation.

When I was a child, I saw many parents forbidding their children from speaking Bhojpuri, saying it was “bad”. Hearing my mother tongue being insulted affected me deeply, and I thought, I have to work with this theme. How can a native language be a bad thing?

Priyanka Singh Parihar Art and activist spaces are not always equitable. What challenges have you faced as an artist from a marginalised community?

Umesh S. English plays an important role in the art world, and since I don’t speak it well, I face setbacks. People also ignore you if you don’t speak English. In the past, I couldn’t apply for residencies and grants because of this.

But some organisations are creating equal opportunities, like the Foundation for Indian Contemporary Art, Khoj Studio, and Serendipity. But many spaces remain closed, and so many artists leave their practice. In Bihar, UP, Jharkhand, and Madhya Pradesh, around 130 children enrol in fine arts courses at BHU, but only one percent continue their practice because they don’t see a future; they start looking for jobs, thinking it’s beyond their means to be an artist. It’s a genuine problem.

There is a deep interconnection. It’s important to speak about other animals: earthworms and other small insects are vanishing. If a farm can’t sustain the earthworm, then its food becomes poisonous. This is how we assess land. If it becomes inhospitable to insects, how can it be edible to us?

Umesh S.

Multidisciplinary artist

Priyanka Singh Parihar Beyond your art, are you also involved in learning or preserving indigenous farming practices?

Umesh S. I’m trying to create a seed-preservation pot. I’m experimenting by leaving seeds in it for a couple of years to see what methods of preservation work, like they did twenty years ago. I also plan to visit villages and search for indigenous seeds from farmers who have preserved them and spread them. We’re losing indigenous plants to the hybrids, like the indigenous guava, which is gone; it doesn’t taste the same. I love fruits, and I’ve eaten many varieties of mangoes, but now these are rare; only a few hybrids are on the market.

Also, the obsolete farming tools are now vanishing. We are not doing anything to preserve it, and knowledge related to it is being lost. I tried to preserve these tools and read about them. Every twenty kilometres across the landscape, the language changes, and so does the tool. I collected these tools and compared them, like why there are differences in sickles. I’m still continuing this research.

Priyanka Singh Parihar Reverence is the deep respect and acknowledgement of the interconnectedness of all beings, recognising the value and significance of every story, culture, and experience. Do you consider your work a reflection of reverence for these connections, and how does that shape the stories you tell through your work?

Umesh S. I find peace in nature. As a child, I spent my days on food-bearing trees: mango, jamun (Java plum), and gavua. We bathed and drank in the river; it was so clean. It was a blessing. The origin of our sacred rituals, like Chhat Puja, was connected to the sun and the river. We can still see the sun and the river, but we don’t revere them. Artificial ponds and man-made temples have replaced them.

There is a deep interconnection. It’s important to speak about other animals: earthworms and other small insects are vanishing. If a farm can’t sustain the earthworm, then its food becomes poisonous. This is how we assess land. If it becomes inhospitable to insects, how can it be edible to us?

This interview was originally conducted in Hindi and translated by the interviewer.