Heredosporium: I was both the Cordyceps and the Ant

But parasitism is not just a metaphor. It’s biology. It shapes forests, fungi networks, and coral reefs. It shaped me. My internal ecosystem. My identity.

Martina Orska

Photographer

“Heredosporium” is an invented term that merges “heredo” (inheritance) and “sporium” (spores). It refers to the invisible yet generative traces of inherited trauma that, like spores, settle, grow, and transform the internal ecosystem over time.

I was both the Cordyceps and the ant, the parasite and the host. Two sides of the same inevitable pain, rooted deep within me.

How deep and how rooted was my depression? Where did it come from?

From within.

From my pain, from my parents’ pain, from the weight of transgenerational trauma.

From my core, pulsing beneath the surface.

Over time I realized I was asking the wrong question. It was not about finding an answer, it was about giving structure to something that was a part of me. I didn’t have the capacity to translate sensations into words. I was exhausted from talking, from endless therapies and explanations. I needed a different language. A visual one.

It wasn’t that I couldn’t explain it. I could. But words stayed abstract. They floated on the surface. I needed to see it. To give shape to something shapeless. Something that didn’t demand clarity or linearity. Because my experience had never been linear.

I craved a form that could hold contradiction, distortion, repetition. That could speak from the inside. One that bypassed language and landed directly in the body.

Nature held the answer, already encoded in everything around me. In the way life adapts, survives, and decomposes. In the invisible systems that live inside and all around us. That’s where I found the language my body understood. Not medical. Not diagnostic. Something more instinctive: image, sensation, transformation.

I came across a video of an ant infected by Cordyceps, a parasitic fungus that manipulates its host from the inside. This discovery deeply resonated. As humans, we are deeply intertwined with nature, how we perceive it and how we find meaning in it.

Cordyceps begins as a sticky spore, waiting on the forest floor. If it lands on an ant, it pierces the exoskeleton with threadlike hyphae. It moves inward. It multiplies. It slowly takes control, guiding the ant to climb, then freeze, then die.

I recognised the process.

The weakness. The invasion. The powerlessness. The shredding silence.

Depression had attached itself to me in the same way. Not overnight, but gradually. Almost gently. A silent takeover. I couldn’t escape it, because there was nowhere to go. Like the ant, I was caught in an ecosystem that nourished its spread—a weak host weighed down by inherited trauma. Every thought, every pain became fuel, allowing it to multiply. An unseen, yet deeply felt colony overtaking my sense of self.

But parasitism is not just a metaphor. It’s biology. It shapes forests, fungi networks, and coral reefs. It shaped me. My internal ecosystem. My identity.

Fungi thrive in decay, breaking down organic matter and cycling nutrients back into the environment. This made me wonder: Could depression, like fungi, also serve a role? Could it be a sign? Perhaps something inside me was ready to break down, to be understood, to be reshaped into something whole.

My understanding of depression began to shift from an external enemy to an internal signal. I began to see it as part of a system, shaped by my history, my parents’ silences, and the inherited grief I hadn’t asked for but carried anyway.

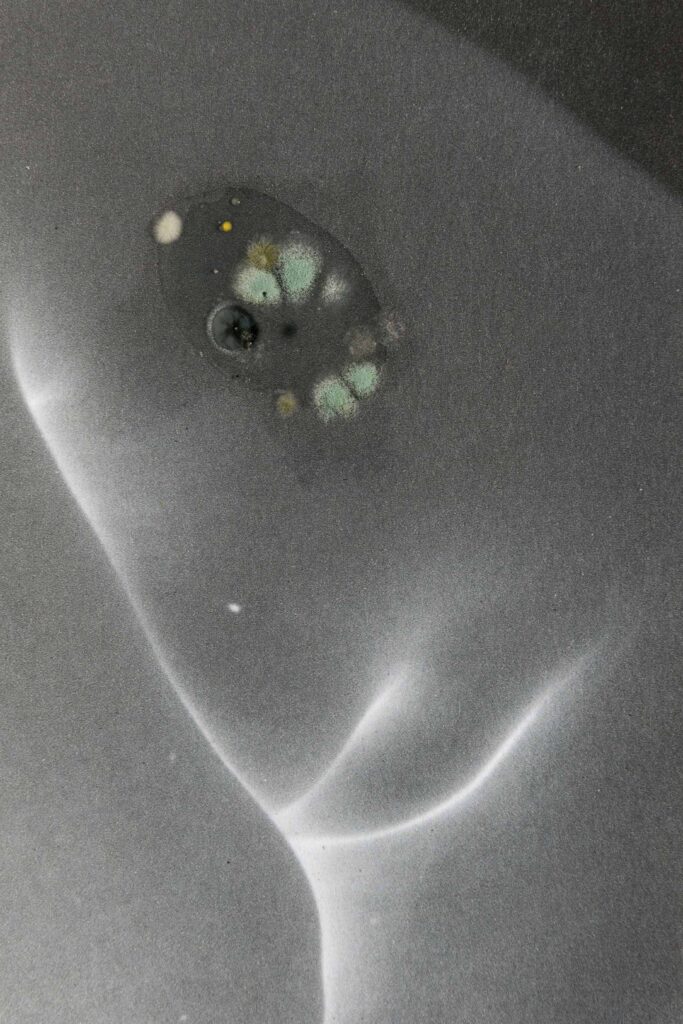

So I turned my own ecosystem into a living laboratory, letting bacteria from my body and fungi from the air colonise my self-portraits. I began documenting the sticky spores growing across the images. The natural world crept across my face, as if my very existence were being overtaken. I created the perfect environment for decay: warmth, stillness, time. I watched as mould and spores overtook my image, my eyes, my lips, my hands, and my identity. Some days, I felt the symptoms return. The weight. The exhaustion. The feeling of being completely broken.

One day, without fully planning it, I took the portraits out of their humid home and placed them in a dry space. The bacteria died. The fungus died. Dust was all that remained.

The images were still marked—but no longer alive.

What once consumed everything now lingered like a memory.

A quiet residue.

I could see it.

I could touch it.

And I could brush it away with a finger.

But I could still see its trace. I could see what it left behind. It left who I am.

Decay is never the end. In nature it’s part of a larger cycle. Just as fungi break down what once lived, transforming it into fertile ground for renewal, perhaps suffering too can be repurposed. Depression is not just a personal affliction; it is part of a larger system, shaped by history, lineage, and the ecosystems we inhabit.

For a long time, I imagined depression as something that came from outside. An invader, a foreign force. A thing to fight. But the more I worked, the more I understood: the Cordyceps was never a stranger.

It was me.

I was both parasite and host. The trauma and the body. The one who was overtaken and the one who allowed it to grow. They’re not separate. They coexist. And in that coexistence, I began to change.

A part of me broke down. And maybe it had to, to let another part grow.

Words and Photography by Martina Orska

Martina Orska is an Ecuadorian photographer based in Barcelona. Her work bridges folklore, materiality, and the body, often through hands-on experimentation. While she has worked in still life and fashion, this project comes from a more intimate part of her practice, where photography becomes a means of processing what we carry, individually and collectively.