We offer our ancestors to this river; with her flows the spirit of our loved ones, the ones that are gone but still revered along with the river. Every time we take a dip and trust the river to cleanse us from our burdens, we are essentially trusting the spirit of the river, which has become inseparable from the spirit of our loved ones.

Priyanka SinghLife & Death by the Ganges: The Flow of Ancestral Spirits | Priyanka Singh

It was a few hours past midnight, and I was asleep in the car. We traveled for long hours, and my family woke me up at an unusual hour. Immediately after waking up, my father rushed us to dip in the Ganges. He is usually very excited about religious practices. But as a girl in her teenage years, this tiresome journey was not making sense to me. The abundance of animal dung and garbage around the river was a cause of my distress.

We repeated these rituals year after year, in the warmth of the sun and the quivering winter. Seasons change, but the devotion of a Hindu family to take a dip in the Ganges is much like the melodies of the songbirds. They remain consistent. A few days ago, I stumbled on the fact that songbirds have to practice their songs; similarly, for us, devotion is only perfected with practice. I wonder how many dips my father has taken to begin to find joy in this practice.

It is not just our story, but the story of the Hindus and their gods. They often decorate their gods with the colors of the sun (red, yellow, and saffron), and they worship them in infinite forms: in idols, in rivers, in mountains, and in trees. In its living form, nature is personified and revered; one of such personifications is the Ganges.

Why do we worship the Ganges? I often wondered. Pilgrims from all around India and, surprisingly enough, white people from the West travel to reach the holy ghats of the Ganges. I think all the rivers, seas, and oceans have a life force within them that resonates with our primitive instincts. But the Ganges’ connection to death and the afterlife deepens this resonance. These parts are the ones that you begin to realize once you witness a few deaths, a few stories that are coming to an end but will flow for indefinite centuries, or perhaps for what will seem like an eternity in human life years.

There are many cremation sites across India, but the Manikarnika Ghat in Varanasi, located by the Ganges, is the oldest and most sacred. Witnessing the endless number of cremations each day, body after body, coming across from India to reach this Ghat, we believe that one of the greatest honors for a Hindu devotee is to die and to cremate on this land. Upon arrival, the bodies are submerged in the Ganges, perhaps for the final bath, and then the family (only male members) will offer the holy water to the deceased with their hands.

Each year, we prepare meals for our deceased—each plate for the ancestor we could name—and we believe they come to enjoy this food prepared by their loved ones from the afterlife. Though there is a specific time when this ritual is considered auspicious, you can always find families performing this particular ritual by the Ganges in gratitude for their ancestors.

The story says that Mata Sati sacrificed herself here by igniting a fire and departing to the afterlife, leaving the fire behind. This fire is still blazing. The ”Doms”, a community in Varanasi, have kept this fire alive for almost 3,000 years, lighting every pyre since then.

The tales of the doms in Hindu society are another great mystery.

The doms were considered the scheduled castes—the untouchables of ancient India—who were looked down upon by higher castes and not to be mingled with. How strange it is that we ought to maintain distance from these people, yet we give them and only them the rites to perform end rituals for our deceased—they are an integral part of closing our life cycle as we begin our journey to the other side. The Doms understand fire and maybe death better than most Hindus do. They live by the fire, generation after generation. They are the keepers of the cremation grounds and take pride in their duty as any Brahman (priest) does in his. I asked them if they ever wished to leave to seek something else, but most seemed very connected to the fire and with the warmth that might burn the ordinary.

They take the ashes to the Ganges and bathe in the spots where the remains of the deceased blend with the water in search of gold or silver adorned in the bodies before the cremation. This whole process of looking for precious jewels seemed like a joyful activity. After the warmth of the fire, the river offers its calmness, and the deceased offer the jewels that once used to be theirs.

We believe that our sins will vanish if we bathe in the Ganges. I don’t know if that is true since it is a matter of belief, and belief is realized and then cultivated. It’s much more than word of mouth; it is a matter of shared stories for generations. However, being by the Ganges eventually made me realize we offer our ancestors to this river; with her flows the spirit of our loved ones, the ones that are gone but still revered along with the river. Every time we take a dip and trust the river to cleanse us from our burdens, we are essentially trusting the spirit of the river, which has become inseparable from the spirit of our loved ones.

When we lose a loved one to the most certain truth of life—death—we seek them in many places. We often dream about the dead to make peace with their departure, listen to their stories, listen to the music they enjoyed, and read the book they once read. We slowly begin to find closure, sometimes by believing that perhaps we unite with them in the afterlife or when we can feel their presence in our hearts when we are in the bliss of oneness.

Even if they are gone, they walked these lands, bathed in these rivers, and inhaled this air, and even after their deaths, their energy remains a part of the ecosystem. When we begin to respect nature as a spirit, we realize that by worshiping the Earth, we are not only worshiping her vital energy but also the spirits of our ancestors and of our children, who will find our presence on this land much longer after we are gone.

Reverence requires a deep devotion far beyond the flesh. The river never stops flowing, day or night. She moves constantly in darkness and light, moving forward, reaching the terrain, blessing the bees, and bringing the rain. The river is devoted to the life force as we are to her, a mutual practice. On this journey of finding hope that we might love and nurture, or at least attempt to heal, the flowing rivers, oceans, and forests, I sometimes feel disheartened, but the river only knows how to move forward and does her part. So I have to be grateful to do mine until the day when my ashes merge with hers, and then it will be the beginning of a new cycle.

In memory of my grandmother, who passed away a few days before I visited India, she now flows with the Ganges along with many of my ancestors, whom I might not even know by name.

My grandma was 96. She spent her entire life in a village, walking on her crutches, and she mostly seemed content. Perhaps if I never knew about the melancholic realities of the current time, I would be content too, but I cannot unsee what I have already witnessed. My grandma would take care of the stray puppies even with her unconscious aging body, so I hope I can be like her, and even if the end approaches, I could still be content with the fact that I was able to care for something with all my heart.

Words by Priyanka Singh

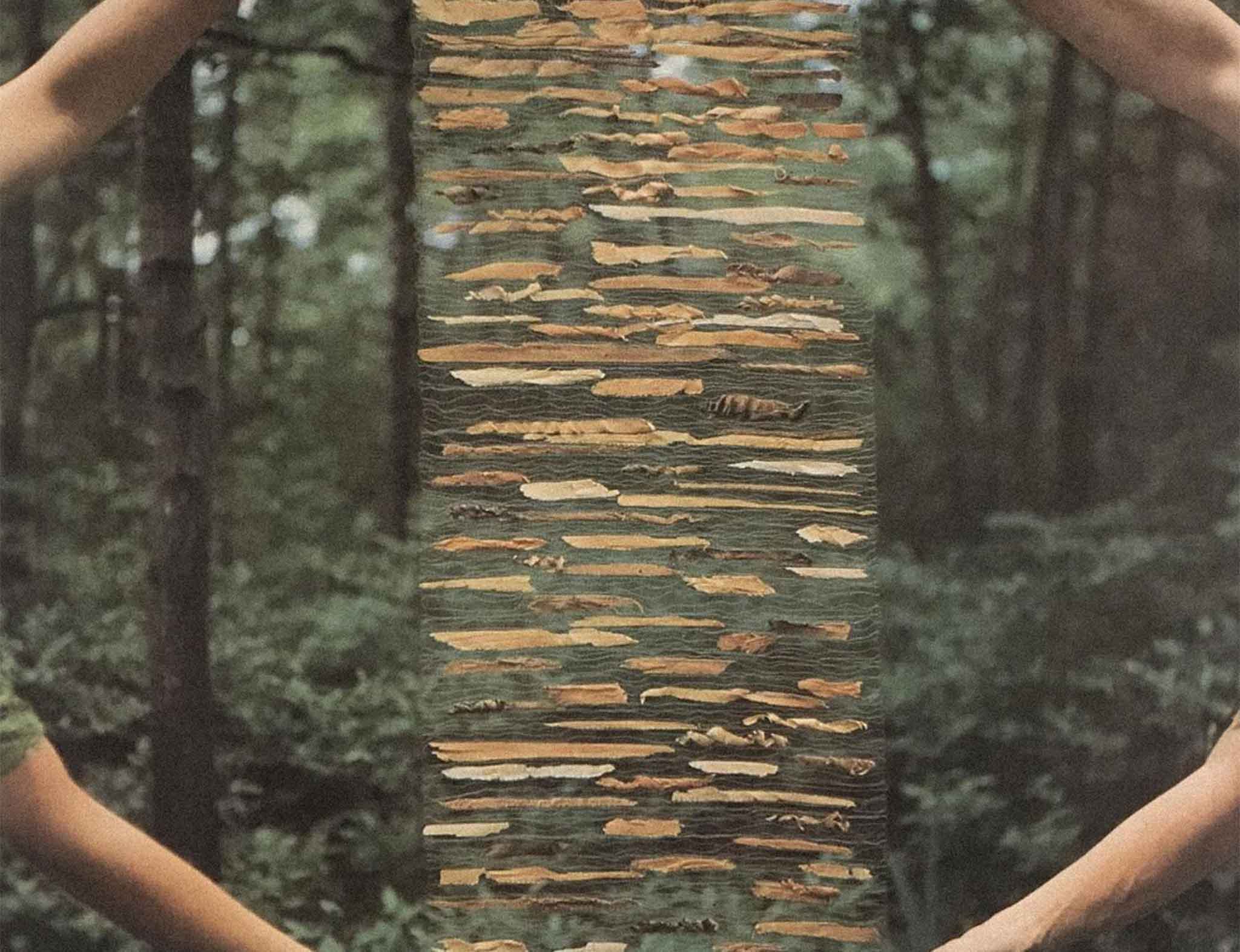

Photos by Anubhav Gupta