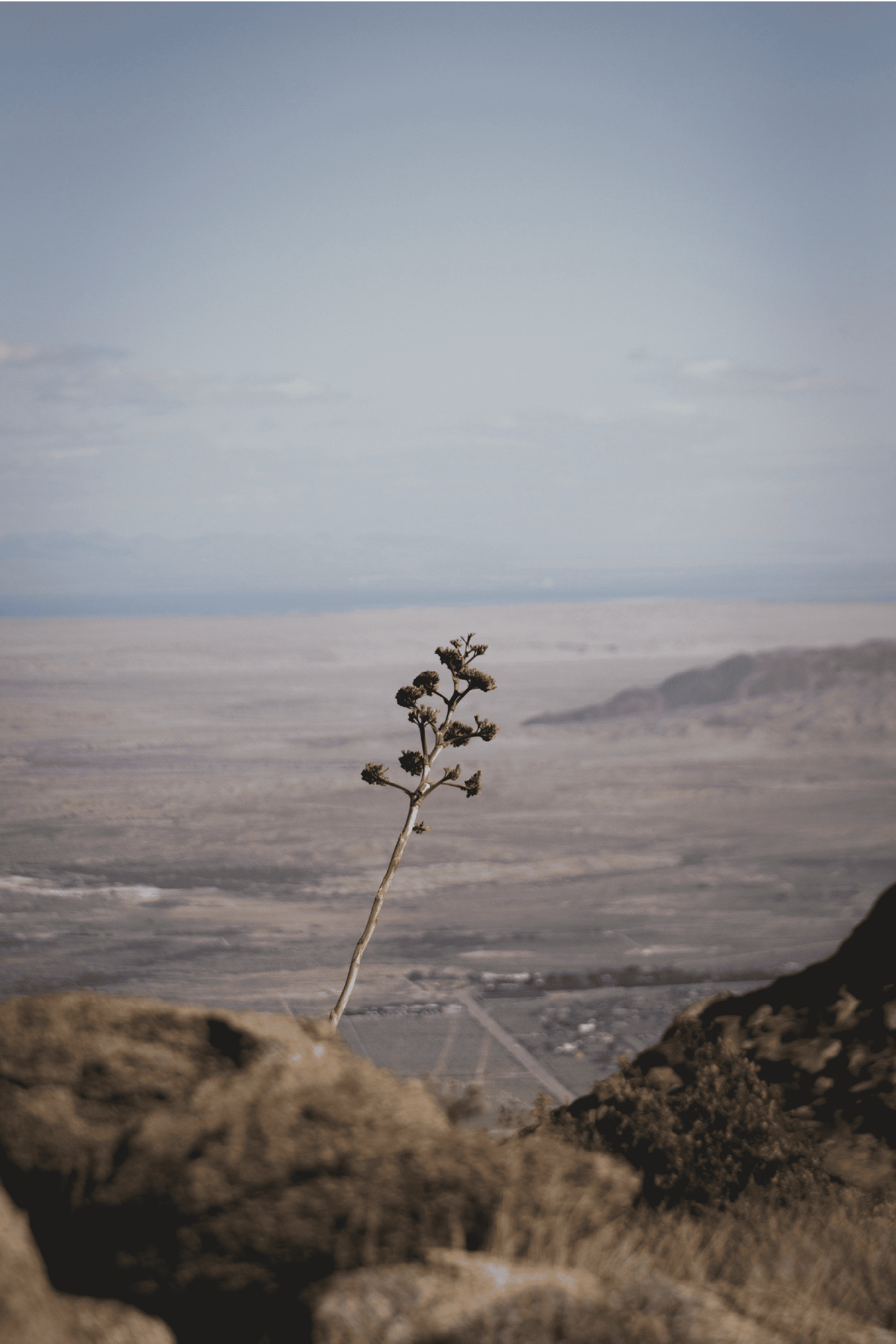

What if landscapes were alive—moving through the passage of life? A painful birth, followed by an adulthood that shapes character; and even when time appears to stand still, flowing rivers deepen valleys, glaciers retreat, and mountains continue to rise. Upon the death of a landscape, a new story begins, birthing a new memory.

A family of mountains was born in a messy collision of two continents. The Himalayas rose when the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates collided, thrusting the land upward, reaching the sky. They still rise, like a growing body in adolescence. This vast living system stretches across political boundaries, transcending man-made meaning, a home to rivers, glaciers, and valleys shaped in deep time.

The glacier is melting; millennia flow in fleeting moments as meltwater quenches the thirst of apple trees, bears, and humans. The River Ganga, in her infancy, originates from the headwaters of the Bhagirathi River, flowing fiercely and carving valleys. At Devprayag, the confluence of the Bhagirathi and Alaknanda Rivers shapes the Ganga in her youth. From here she ages, moving slowly with the wisdom of an elder, reaching the plains where she is revered through fire, flowers, and chants. The dead are cremated along the ghats, and bodies are returned to the ageing river.

Elsewhere in the same Himalayan body, another life is ending.

On May 12, 2025, the chilling wind blended with the scent of incense amid Buddhist chants in Nepal’s Langtang Valley, paying tribute to Yala, a dying glacier. The ceremony closed the gap between science and spirituality: scientists and monks gathered in the presence of a receding glacier revered by local communities as the home of the gods. Among the family of nearly 15,000 Himalayan glaciers, Yala is the first officially recognised dying glacier. Its retreat is accelerated not by natural cycles alone, but by human-driven climate change.

These rituals of reverence and grief toward the landscape are innate to humankind. They are instincts older than science, allowing us to understand and connect with the world around us. Contemplating the material world, which includes forests, trees, mountains, and animals, once helped us survive as a species. We knew which plants to consume, where to take shelter, and what to avoid because we understood the landscape.

Even though we have largely forgotten this connection, across cultures we still return our dead to land and rivers. Why, then, does the separation between culture and nature exist? Why is the human body not acknowledged as part of the Earth? Why do urban landscapes remain distant from natural environments? To answer this, we must look at the definition of nature.

The Oxford Dictionary defines nature as “all the plants, animals, etc. in the universe and all the things that happen in it that are not made or caused by people.” But imagine removing any other community of the natural world, for example, birds or bears. It would then read: “all the plants, animals, etc. in the universe and all the things that happen in it that are not made or caused by birds or bears.” This feels unsettling. Why, then, does the expulsion of humanity from nature seem “natural”?

According to environmental psychologist Joanne Vining, this dualism between humans and nature is rooted in the myth of the fall and humanity’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden, separating humankind from the rest of creation. Ancient people often saw nature as divine in its separation from humans. Even if this division was intended to bring humans closer to spiritual fulfilment, it ultimately materialised into a culture that forgot nature.

Returning to the living landscape, whether through mourning glaciers or becoming aware of a changing world, once again places us as active participants in shaping the natural world we inhabit. The word landscape itself reflects this agency: land combined with “-scape”, related to the English suffix “-ship”, meaning “to shape”. Grief, then, is not merely an expression of loss but a recognition of relationship—a guide to what we truly love and a new cultural memory in the making, where humans belong within nature.