Alphabet ‘A’ originated from the symbol of an ox ‘Ɐ’, M from waving water ~~~, N from a twisted snake, and O from an eye. Although English is a colonial language, within it are the worlds that we have long forgotten. An amnesia that torments the past and the present alike.

Egyptian hieroglyphs were a sacred writing system. Its symbols were derived from the surroundings – nature, animals, human bodies, and everyday objects. It is here that the immaterial began translating into the material; abstract symbols carried sounds. The world that silently spoke to the human consciousness now had a form. The Latin alphabet grew from those roots, crossing seas as merchants carried messages. Now these symbols, in their new avatar, sit in the tongue and rest in the hands of modern humans. Spanish, French, Italian, German, Turkish, and the most widely spoken language, English, all share the Latin alphabet.

If we look past the colonial lens, perhaps there was a time when the English language was in its innocence, perhaps even carrying deep reverence towards the living world.

In the past I have written about the origin of the English words that have resonated with me, such as ‘animal’, which relates to the Latin ‘anima’, meaning ‘soul’, and ‘spirit’, which comes from the Latin ‘spiriare’, meaning ‘breathe’. ‘Human’ is from the Latin ‘humus’, meaning ‘earth’, and ‘soul’ is from the Proto-Germanic ‘saiwaz’, meaning ‘belonging’ to the sea’. And I’m certain if I keep digging deeper, in search of other roots, I will find a living, breathing, and wise intelligence of nature that delves within this language.

I learnt about the colonial history of my country, the geography of divided lands, and the catastrophes of the changing climate, not in my mother tongue but in English. I couldn’t see it back then, but now I know that even after more than seven decades of independence, linguistically we remained colonised.

There is a sense of irony and shame that I write in English and not in Hindi, a language that remains in the shadows for Indian schooling systems. For someone practising writing as an art form, at times I feel challenged. But I’m learning to look beyond that shame because I believe at heart we all speak the language of nature. And if I can decipher even the smallest part of this insanely beautiful living language, I would have done my part in the world.

I have also grown to notice the similarity between Hindi and English, two distantly related languages sharing a common ancestor, Proto-Indo-European (PIE). For example, the Hindi word for nature, Prakṛti (प्रकृति), can signify the natural world but also the temperament of humans, similar to the word ‘nature’, which can hold both these realities. The word Jaanwar (जानवर), meaning animal in Hindi, starts with ‘Jaan’, which means ‘life’. Perhaps here again, the acknowledgement of an animal being a living, sentient being evokes a parallel with the anima of the animal.

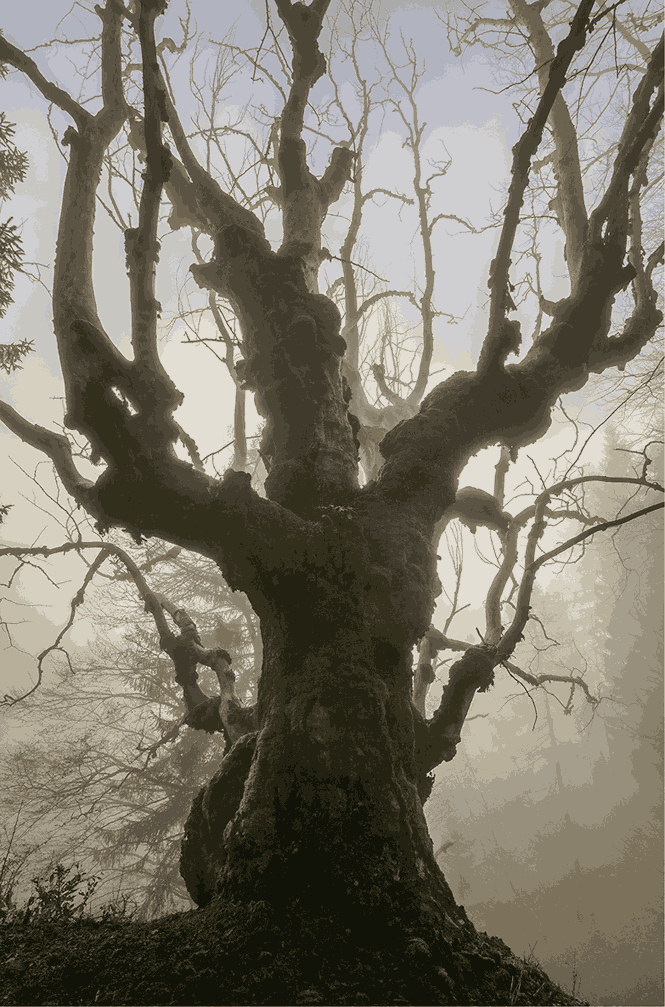

For me, this is a sign that whether it’s our language, our body, or our culture, everything is growing in the same tree nestling human and more-than-human. And yet nature faded from everyday vocabulary. According to a study by Miles Richardson, professor of nature connectedness at the University of Derby, from the 1800s, the use of nature words, ‘river’, ‘blossom’, ‘moss’, and ‘meadow’, declined by 60% in books. Humans write about what they feel connected to; this study reflects the cultural shift, perhaps even the making of the climate crisis.

In spite of this, we are finding our way back. There is hope; nature words in books have increased by 7.6% in the last two decades, shifting the decline from 60% to 52.4% today.

I believe we are listening to the Earth once again. Even after centuries of colonisation, destruction, and catastrophe, we are not entirely lost; there is still nature breathing in human nature. Just like the branches of a tree can only grow as far as the roots reach, we must grow into the world of new imaginings by tending to the roots, whether it’s learning about our own family tree or the lingual tree. I cannot shame a language only as a colonial language if I hope to share the beauty of nature through it. I must look beyond the shame; I must look at the roots that united us long before we were separated from one another, from nature, and from the Earth.

How to Decolonise Language

- Look at the etymological roots; if you find something beautiful, share it with your friends and community.

- Personify nature; talk to the trees, flowers, birds, and even the planetary bodies. The moon makes an excellent companion.

- Spend more time outdoors, smell the grass after it rains, notice the texture, and let nature speak to you.