Salt brings its own metaphors; definitely, healing is one of them. For me, going down there is a healing and a mourning act. You can’t talk about the Dead Sea without meeting some kind of side of death.

Sigalit LandauCrystallising Memories: Poverty Jewels of the Dead Sea | Sigalit Landau

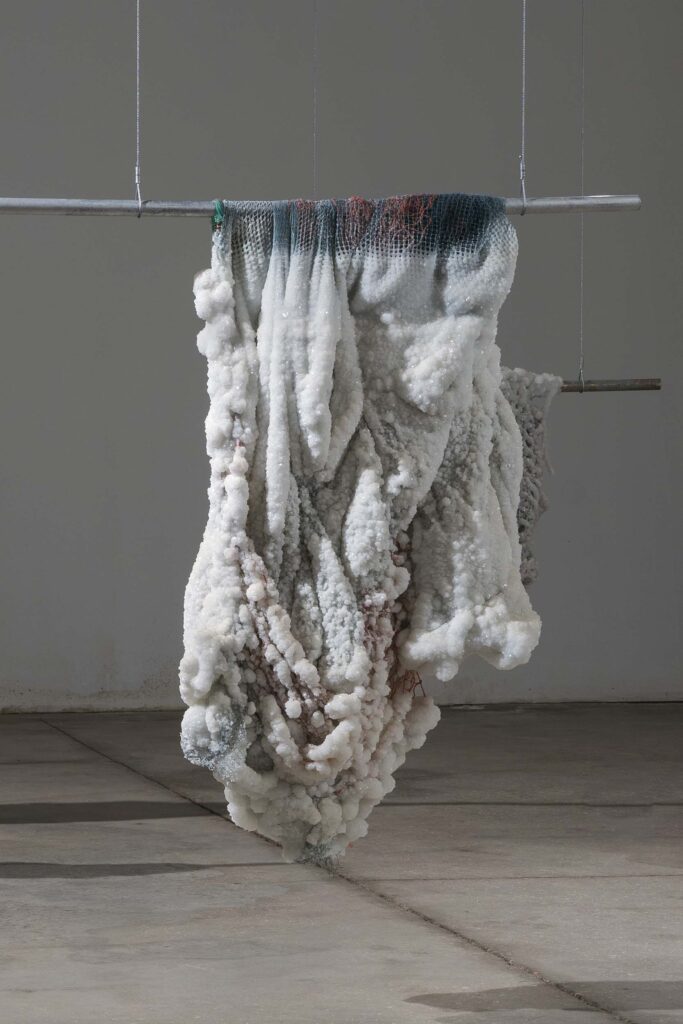

Based in Tel Aviv, Sigalit Landau is an interdisciplinary artist who works with installation, video, photography, and sculpture. Over the years, she has turned the Dead Sea into her laboratory and medium for new explorations. Using the natural process of salt crystallisation, Sigalit transforms objects imbued with unique memories into art pieces—‘Poverty Jewels’.

The Dead Sea is a unique disappearing phenomenon that makes itself visible with time. Its transformative qualities are alluring, but its harsh waters can be a deterrent. How would you describe your relationship with this contrasting environment?

In my world, the Dead Sea divides between the sea I saw during childhood and the present one. The one from the past is a memory, and is very different from today. Because the sea has disappeared so much since I was a child. You can even say it’s part of my body and my upbringing. I have been a witness for over 50 years. Jerusalem is not far from the Dead Sea. In the part where I grew up, I could see the sea from the bedroom and my window because it used to be much larger. You know now that it’s winter here. In winter, the sea is very spiritual and serene. “A pleasant place.”. When it’s summer, that’s when we are working at it. It’s the sun that we are afraid of. In water, we need a certain temperature. Once we begin, there are a lot of technical and scientific sides. Before the result, there is so much waiting, even though it’s a process of waiting. The temperature needs to rise while a part of the work is inside. There is a survival mode. When you come into something so concentrated,. It’s not just salt in the water. There is much more than salt. It has chlorine. It’s kind of a laboratory. But a mysterious one even scientists come to ask. They really go on with my work. If we manage to get something out of the water, then that’s the moment when we are usually very surprised. There is always this unknown, and once it’s known, it becomes more beautiful. The nicest moment is when it’s glistening; that’s when the sun turns this frozen look into something. It simulates the dimension of whiteness in snow.

You walk down memory lane to select materials for your salt sculptures, like ballet dresses, barbed wire, fishing nets, etc. Does that choice come from intentionality or subconsciousness?

It started as a memory, but then I followed the material. Some works, like stretchers, are more collective memories. I will have these decisions and experiments, which will completely be in my subconscious. After it comes from the subconscious, it still needs a lot of work. The intention is to motivate and educate you. I am researching my subconscious, but once it’s out in the world, it’s conscious.

Time is the key to your sculptures, with salt as a metaphor for the passage of time. Do you see the act of Crystallising objects as a constant longing or healing a wound?

Geologically, of course, it’s crystallised. It behaves more like a wound. The image blurs. Some of the things you didn’t see before, you see after the salt is there.

Salt brings its own metaphors; definitely, healing is one of them. For me, going down there is a healing and a mourning act. You can’t talk about the Dead Sea without meeting some kind of side of death.

There’s something beautiful about death. It comes as some sort of frugal sovereignty. In Judaism, the corpse is covered with a white cloth, and so is the bride, covered in just a white dress. Something is born, but something is dead in this process. With all due respect to metaphors, it wouldn’t be so otherwise. It wouldn’t have this cathartic and healing effect on me and my world. The way I make other works. I even make bronzes, pianos, and many figurative images that are difficult to look at. The energy of my salt works is so different from the other works. Through my very first work, “Dead Sea,” I discovered crystallisation and started making sculptures. But that work already wanted to be some kind of vehicle between one side of the rift valley and the other side of the rift valley to connect the two worlds. You can feel the fact that you are in a very special place—an opportunity to think differently about the situation, nature, and beauty.

The sculptures are a result of natural processes. Do they continue to evolve? If so, have you ever reflected on them being alive?

Depending on air pressure, altitude, and humidity, of course, affects the work. Even if the work is drying, the process continues, so I need to remember that there is always something ongoing. There is also a longing for the moment in which it was made. Salt has its own ageing process. It’s called curing. What we are doing here is really an experiment. It has a spectrum of what it wants to be. Where will it finally end up?

Does the mystery of the outcome still thrill you, or has the long familiarity with the Dead Sea left no place for distrust?

There is always this newness about every piece and every summer. There is no way that I can predict because every year it’s a little bit different and crystals form the way they want to. So, I think I have seen it all, but I realise I haven’t seen it all. Once the work is underwater, how long do I leave it inside, and if I am going to make a few levels? Sometimes I want to emphasise the vertical lines, so during the time it’s inside, I change and edit.

It’s like talking to the sea and the different impacts that it has on something.

I trust the sea, but part of the work that we make doesn’t make it to the studio. There is this big effort and some reward. There is always something tricky, so I don’t trust it completely. Every year we come, and we find the landscape so changed because the sea is receding. The dehydration pools are where we work. They are not exactly the sea. They are the pools where the industry pumps. So, I have a whole level of strange administration issues. The artist just wants to work in the water, but I can’t reach the water in the north because of the sinkholes that are happening all the time. The dominance of this corporation means I need their permission to use their jetties, and that’s funny because it’s the border. There, it’s like collaborating with an army, and I am walking towards the border just for my own world to be enabled.

In an interview, you mentioned that ‘the Dead Sea used to be a friendly meeting point for people from Jericho, East Jerusalem, Arabs, and Jews’. Do you think there is a possibility that the Dead Sea—a wonder of nature—could again become a place for these friendly meetings?

Recent events following the October 7th massacre and the invasion of Gaza have changed everything in the area. I know that one day people will see the Dead Sea as crossable, but not in my lifetime. Hundreds are killed and wounded daily. Despair is taking over the dreamers, me included.

Amidst the beautiful hues of aquamarine, the Dead Sea is filled with a plethora of glistening white that you carry in your sculptures. Does this glistening white have any meaning to you?

I call them poverty jewels. Salt is such a basic, truthful material. I am working with nature, but it’s not organic, and I think about its fragility.

I grew up in stories, in places that my family had to leave, in a place where snow and ice are. Feeding off these stories and going out into the deserts the pieces are created.

The glistening white is also very diamond-looking, but again, it’s the opposite of diamond. This is the simplicity of it, and there is nothing luxurious about the situation except that each individual crystal has its own size and its own ability to amaze when you come closer to the work in a way. Fragility comes into play when you start working out. It needs readjusting in terms of gravity because there is hardly any gravity until the salt is accumulated. Then it comes out of the water and turns into a different kind of world. If the work is strong enough to arrive at the studio in one piece, then we know that it’s not going to be just a mythological moment of an experiment; it will live in the world as a sculpture as a piece of art.

What kind of movement are you creating on Earth? Would you say your rhythms are in sync with the rhythms of nature?

I feel that I am in dialogue with nature, with the gravity of these composed crystals, which grow unpredictably and which we tow from the lowest place on earth to transport personal narrative. It expresses the difficulty of grasping the disappearance of this body of unique waters.I am bound by the seasons. I expose myself to high temperatures every summer. A strange nature indeed, which is lifeless and non-organic but responsive to a mission. I learned a lot by listening to the Dead Sea and working in it as a team—salvaging these miracle teary diamonds.

Interview by Vanshika Agrawal