Everything that exists on the visible plane exists on the invisible plane, and the relationship is one of mutualism, symbiosis, and reciprocity so as not to lose balance. The "disconnection" with the invisible is also a colonial invention that demonised ancient wisdom and replaced it with a system of political, mental, and spiritual control.

Martha Hincapié CharryRenewal of the World: Movement & Rituals for Decolonisation | Martha Hincapié Charry

Born and raised in Colombia, Martha Hincapié Charry is a performance artist, choreographer, and independent curator now based in Berlin.

For over a decade, living in Berlin, Martha has been bringing the practice of indigenous movement and dance to the European continent, cultivating a profound understanding of the body and the planet. Her works address the themes of extinction, the climate crisis and colonization while creating a dialogue between continents, countries, and cultures.

We interviewed her to understand her notions that embody indigenous wisdom and movements.

What made you explore traditional dance forms?

I was born and raised in Colombia. Traditional dance and music is impregnated everywhere. Even when we don’t realise it. My lineage is indigenous on my mother’s side and Afro and Colombian on my father’s side. Some schools in Colombia sometimes offer a glimpse of traditional dance options, and some are part of family parties and social celebrations.

However, it was not until my maternal grandmother died that a journey back to roots, traditions, rituals, and knowledge began.

You belong to an indigenous community in Amazonia that doesn’t exist anymore. As one of the last members of your community, how do you aim to preserve the knowledge and rituals of your ancestors?

My maternal heritage comes from an area where the Amazon meets the Andes.

Officially, my family’s native culture is extinct, and I would only have access to it through books or by visiting museums. When my grandmother left this plane, I felt very clear about her message to return to ancestry, and it was she who left me the keys to start walking towards it.

In the world of ideas, my strategy was to start researching other cultures that had ‘disappeared’ or, rather, were destroyed during the genocidal progress of the ‘conquest’ of the so-called American continent. This led me organically to contact living cultures, which survived all the challenges and continued to resist with their sacred dances and relationships.

I desired to find communities that could adopt me and help me remember what we were forced to forget or feel ashamed to belong to. It has been a long path that has forged me into an extended family.

My generation has been the first to make a lot of family achievements, but what is important is that we are not the last.

The ecosystem is a result of continuous movement such as changing seasons, winds, migration, etc. Do you believe that understanding our bodies in the spectrum of these movements could be a starting point for establishing a connection with the ecosystem?

In the last few years, I have spent long days in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, in the region where my father comes from.

The native cultures of this Sierra, heirs of the Tayrona, see this structure as an oracle of the planet; every single ecosystem that exists on Earth thrives in the Sierra Nevada mountains. Hence, they refer to this area as “The Heart of the World”. Furthermore, the Sierra is also sensed as a mirror of the human body, starting with the feet where the mountain comes out of the sea and ending at the head, the snow-capped peaks. Damaging, amputating, or contaminating any part of the Sierra is equivalent to wounding a specific area of the human body.

In all native cultures, the interconnection and interdependence with the territories is a daily reality. Our separation from nature is a colonial fiction, an imposed narrative that normalises the power to harm the land, assuming that by doing so we do not harm ourselves.We are not ‘disconnected’ from ecosystems. We just need to remember and reclaim our intrinsic relationship with nature. We are nature.

A capitalistic society thrives on being productive, even at the cost of our personal and spiritual health. Why is slowing down an essential healing process for oneself and nature as a whole?

For me, slowing down, going backwards, and holding on is where the real progress is—the future, the opportunity. In these complex times, where multiple global crises are looming (economic, environmental, migratory, social, poverty, health, etc.), the Buen Vivir of the Andean and Amazonian peoples is consolidating as an alternative proposal to the current system based on the western extractivism of human and more than human beings. This situation, added to the gradual loss of rights for people and communities, highlights the urgent need to change the current model. People are increasingly dissatisfied and unhappy, so we are questioning the meaning of imposed models, and more and more local, sustainable initiatives are emerging that seek ways to respect Mother Earth, simplifying life for greater enjoyment in balance and harmony.

The imposed narrative is not reality, as we are in a pluriverse and we have the power (free will) not to consent to it. We can begin our thinking by simply acknowledging our sovereignty and declining any contract we have consciously or unconsciously accepted.

How, according to you, migrating to Europe could be a vital source of the decolonizing process?

Europe has benefited from the exploitation of the rest of the planet and still finds it hard to share its privileges and extracted wealth.

We are not immigrants, we are expelled from our territories, wounded by colonisation. Perhaps we have not come to Europe out of our own desire but rather out of necessity. For all that, the processes of the last 500 years have cut us off, emasculated us, and denied us.

It is our right to be here. Europe needs us more than they know.

Europe needs our humanity, our knowledge, our life force, and our sacred dances. Beyond cultural appropriation, we are here to confront them and to stand in front of the privileged white bodies as a mirror.

Colonisation did not end; it mutated and camouflaged itself, rebranding itself to become normalised and accepted. I don’t claim it. We are here, even though they tried to exterminate us. We are seeds, and our spirits are unbreakable and incorruptible.

Through your art practice, you focus on the critical relationship between the visible and invisible worlds. What do you consider the invisible world, and how are we connected to it?

Everything that exists on the visible plane exists on the invisible plane, and the relationship is one of mutualism, symbiosis, and reciprocity so as not to lose balance.

The “disconnection” with the invisible is also a colonial invention that demonised ancient wisdom and replaced it with a system of political, mental, and spiritual control.

Our relationship with Spirit/Source/ Creator needs no intermediary institutions.

Spiritual

Spirit + Ritual

How can movement or dance be a way to raise awareness about the climate crisis? Do you practice your art with this approach?

Dance and movements are linked to the climate crisis.

The disappearance of spiritual knowledge, which includes dances and rituals of offering, payment, and gratitude to nature, has a consequence for the disappearance of biodiversity. At the same time, the disappearance of biodiversity hinders the execution of rituals and dances of offering, payment, and gratitude to the cosmic mother.

The role of dance on the physical plane and the spiritual plane is of vital importance. It is also in the ritual to dance under the stars around the ancestral fire where the visible and the invisible are juxtaposed, feeding each other.

What kind of movement are you creating on Earth? Would you say your rhythms are in sync with the rhythms of nature?

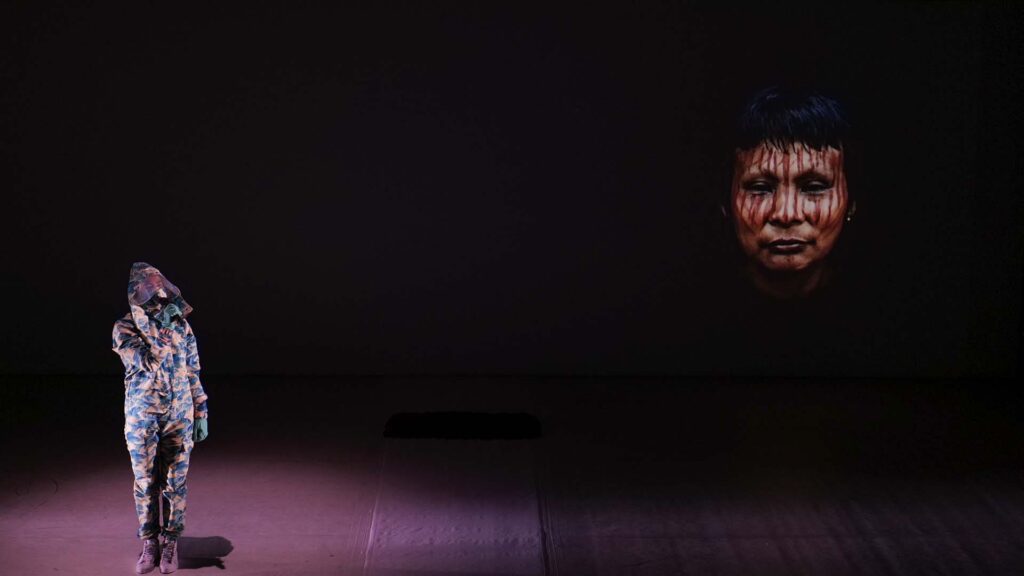

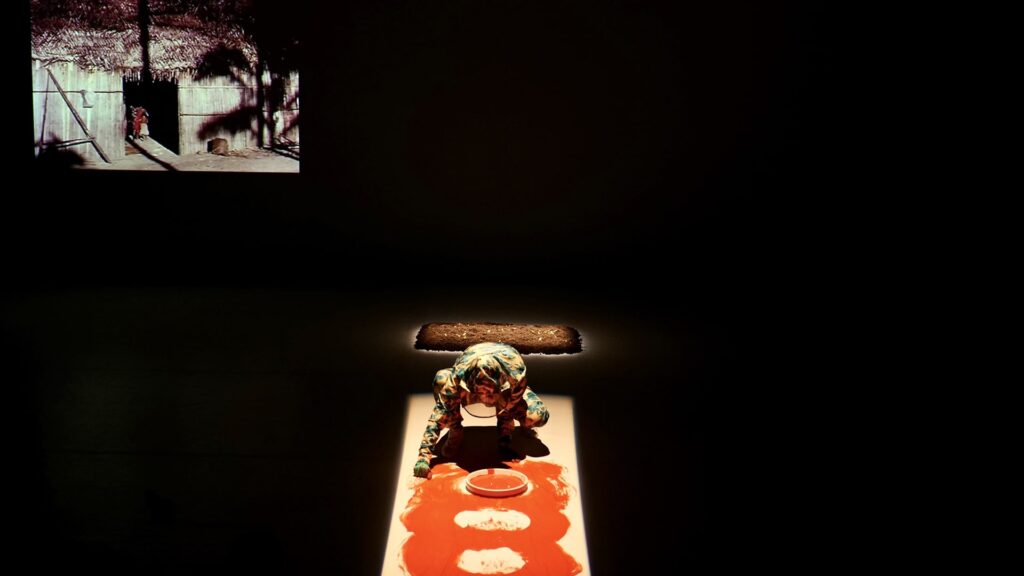

In recent years, I have worked on the trilogy HECATOMB—movements and rituals for the renewal of the world—which brings together live and virtually indigenous leaders and shamans from the so-called Americas who share knowledge and wisdom of their ancestors, expressing it through traditional dances, songs, rituals, and ceremonies, raising awareness about the current crisis in our relationship with nature.

I share performances in a hybrid format where participants have intimate encounters with the indigenous leaders and shamans. This proposal recognizes ancestral indigenous knowledge as a science based on healing technologies that seek the balance of the planet.

Opening a transversal dialogue, HECATOMB attempts to decolonize contemporary dance practices, creating a space for reflection on the relationship of humans with nature and the consequences of everyday actions in terms of climate collapse and the disappearance of habitats, species, and groups of native inhabitants.

HECATOMB reflects on the fact that indigenous people protect 80% of the world’s biodiversity, even though they make up only 5% of the world’s population.

The indigenous leaders and shamans speak from an autobiographical perspective about their origins, their communities, their struggle for survival, and their efforts to defend and protect nature from new forms of colonialism, such as international corporations, the burning of rainforests, the destruction of sacred species like the jaguar, or extractive practices such as mining in sacred lands. Part of their struggle is to perform tribute offerings to the Earth, which are meant to restore balance and harmony between humans and the Earth. Those tributes are currently endangered.

My solo performance AMAZONIA 2040, developed during the pandemic, reflects on the present, past, and future of the Amazonia rainforest and explores the expression and resistance of concepts such as home, habitat, and inhabitants in times of climate crisis, activism, and the disappearance of biodiversity.

Interview by Priyanka Singh Parihar