Fertile Dreams: Exploring Land, Transformation and Ritual in the Middle East

Surrendering to the subconscious and letting instinct guide the hand and shape creation; delving into the earthy terrain of the subconscious mind as if it were animated by soil and roots; allowing creativity to flow in a state of spiritual meditation.

These are the explorations that characterise Fertile Dreams, an evocative exhibition of artworks that blur the boundaries between the material and the metaphysical, guided by the ritualistic intuition of the artists and inspired by nature as a life force of renewal and erosion. The artists integrate the rich and ancient traditions of the MENA region into their artistic practice, exploring the liminality between soil and psyche, land and self, searching for something beyond reason.

The artists explore these themes through different mediums and materials, connecting with the physicality of transformation, imperfection, and change. In so doing, Fertile Dreams seeks to resist and challenge the extractive logic commonly applied to relationships with nature, each other, and oneself.

Within the MENA region and its diasporas, artists are often socialised within rich traditions – oral, spiritual, and artisanal – that subtly inform the psyche. These inheritances surface through instinct, becoming part of the artist’s unconscious vocabulary. The exhibition brings together these interior worlds, where the automatic act of making becomes a channel between the individual and the collective.

Maliha Tabari,

Curator Fertile Dreams

Leila El Zabri: How did you navigate the interplay between personal unconscious expression and collective cultural memory, particularly within the context of the MENA region and its diasporas, when curating this exhibition?

Maliha Tabari: In Fertile Dreams, I wanted to create space for the instinctive, to let impulse and automatism take shape as a kind of language. The artists move intuitively, often guided by rhythm and repetition, entering a meditative state where gesture becomes thought. In many ways, their practices feel ancestral: rooted in inherited knowledge, yet entirely personal. Within the MENA region and its diasporas, artists are often socialised within rich traditions – oral, spiritual, and artisanal – that subtly inform the psyche. These inheritances surface through instinct, becoming part of the artist’s unconscious vocabulary. The exhibition brings together these interior worlds, where the automatic act of making becomes a channel between the individual and the collective.

Leila El Zabri: What role do materials (clay, textile, pigment, etc.) play in shaping the exhibition’s dialogue between the physical and the metaphysical, or between earth and imagination? How do different mediums act as vehicles for the exploration of fertility and ritual?

Maliha Tabari: Materiality in Fertile Dreams is guided by instinct, an almost primal attraction to earthy substances that remind us of our origins. Clay, pigment, and textile are extensions of the natural environment, materials that have shaped human expression since the beginning. They are humble but elevated, charged with history, ritual, and sensory intelligence. The artists in this exhibition approach these materials with reverence, recognising their fertility not only as matter but as metaphor; each surface a trace of creation, each gesture a continuation of the earth’s own cycles. When pigment bleeds or clay cracks, it speaks of transformation, of becoming. Through these processes kneading, layering, weaving materiality becomes a form of meditation. It allows the artists to translate the invisible into the tangible, to merge the physical and the metaphysical through acts that feel both bodily and sacred.

Leila El Zabri: How does the exhibition explore the relationship between Middle Eastern spiritual practices and Surrealist automatism, especially considering their distinct historical and cultural contexts?

Maliha Tabari: For me, the harmony between these frameworks emerges through rhythm and intuition. Surrealist automatism sought to release control, to let the unconscious guide the hand. In many Middle Eastern spiritual and artistic traditions, a similar surrender appears through repetition, breath, and ritual, an opening to the divine through movement and pattern. Both approaches trust the process as revelation. In Fertile Dreams, the artists move fluidly between these energies: the spontaneous mark aligns with the measured rhythm of geometry; trance-like gesture finds echo in spiritual meditation. Rather than collapsing one framework into another, I wanted to reveal their shared pursuit—the search for presence, for flow, for something beyond reason. When seen together, these modes form a continuum rather than a contrast, suggesting that the spiritual and the subconscious may stem from the same human impulse to reach inward and outward at once.

Leila El Zabri: In light of increasing environmental crises and ecological deterioration, how can art, and specifically the themes explored in the Fertile Dreams exhibition, act as a force for social change in the world? What is the role of art and creative expression in the ideation of a world where humanity lives in harmony with nature and its beings?

Maliha Tabari: I see art as a means of restoration, a way to reawaken empathy for the planet and for one another. Fertile Dreams encourages reflection on our connection to the earth, to the body, to feminine energy and to the ecosystems that sustain us. Fertility here is not only a metaphor for creation, womanhood and the power that lies within the feminine but a reminder of reciprocity and renewal. Many of the artists approach nature as collaborator rather than backdrop, allowing imperfection and decay to enter the work. In this lies a quiet resistance to the extractive logic that has distanced humanity from its environment. Art may not change policy, but it changes perception. In doing so, it plants the imaginative seeds for more harmonious futures, worlds in which creation is generated through coexistence.

Fertility here is not only a metaphor for creation, womanhood and the power that lies within the feminine but a reminder of reciprocity and renewal. Many of the artists approach nature as collaborator rather than backdrop, allowing imperfection and decay to enter the work.

Maliha Tabari,

Curator Fertile Dreams

Leila El Zabri: Your abstract landscapes often blur the boundaries between inner and outer worlds. In Fertile Dreams, how does your art mirror the act of dreaming or remembering? How do physical senses, such as sound, scent and touch shape your creative expression and your exploration of self?

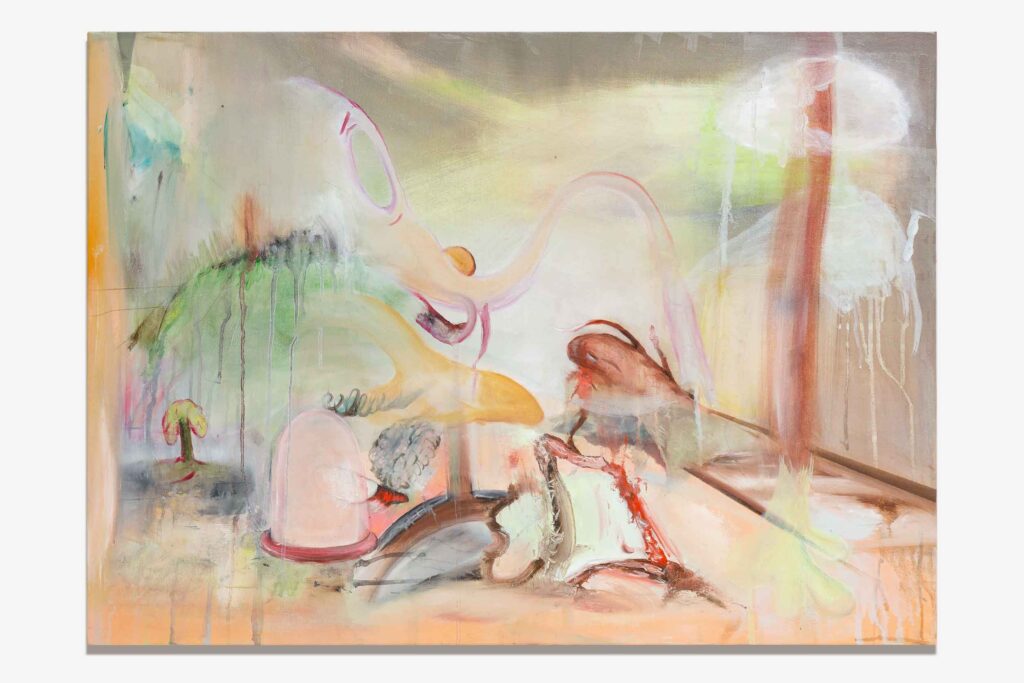

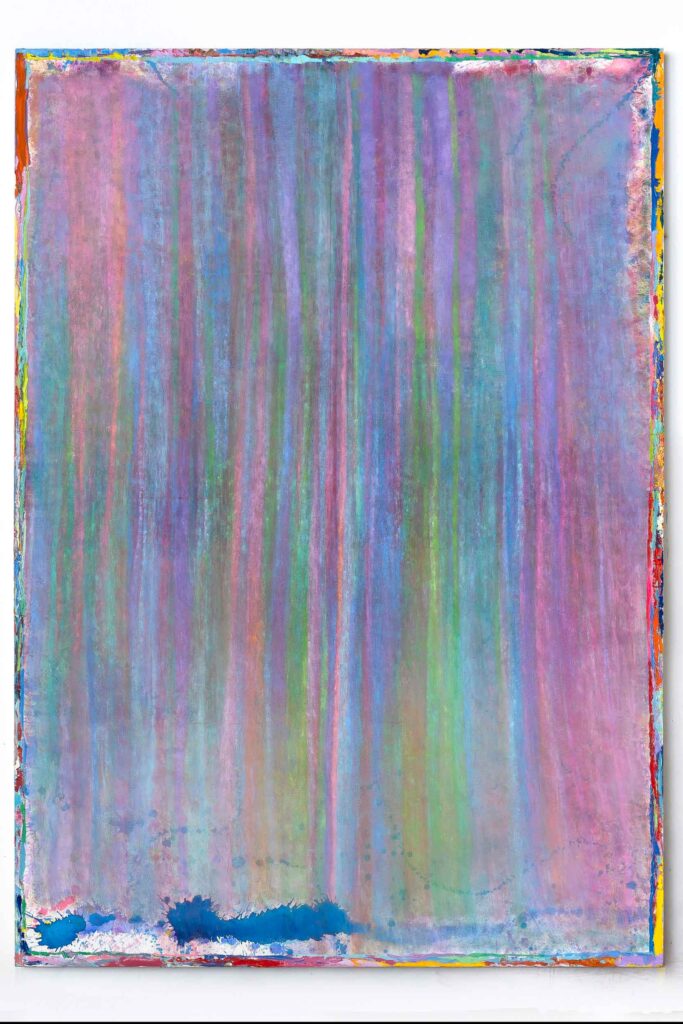

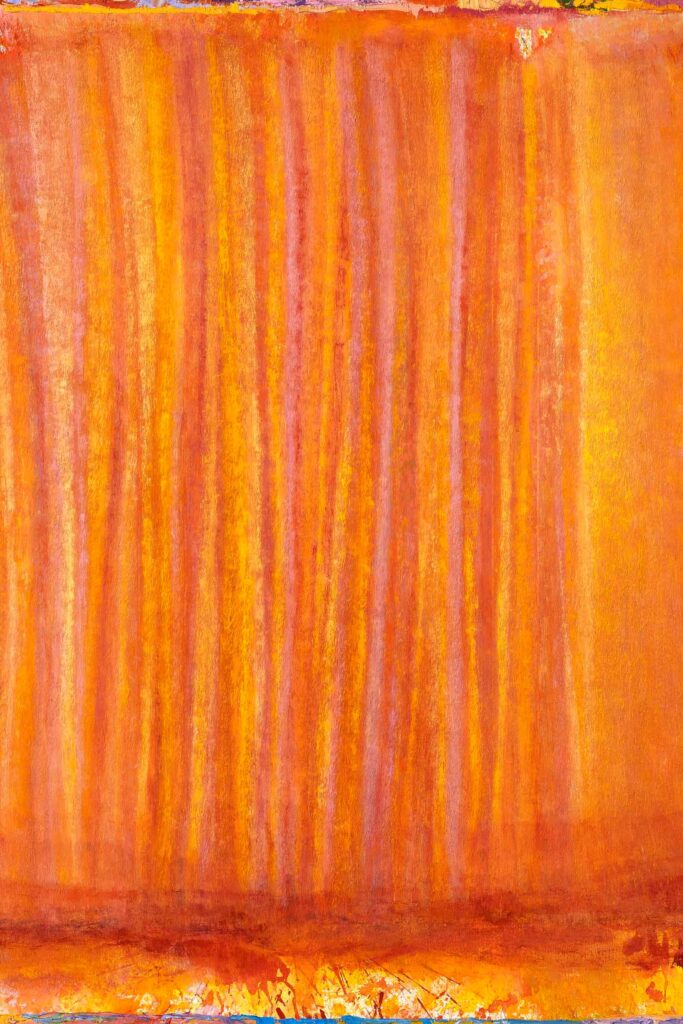

Rema Ghuloum : My paintings are experiential and reflect states of being. I consider them to be more like atmospheres than anything else because they shape-shift depending on what one brings to them. They capture the essence or feeling of a place or something familiar that words fail to describe accurately, much like dreaming or memory. Liminal spaces that exist between internal and external worlds are what interest me most.

Memory functions in multiple ways in the work. I might have specific sensory associations with a color that directs a painting or a feeling that correlates with a palette that I will begin with, but it isn’t fixed. It is a starting point or a guide. Involuntary memory can also be triggered unconsciously when I am developing the paintings or when one is viewing them. This interests me because it allows for a kind of time travel within the work. We all carry our own experiences with us when encountering artworks. I love that. I don’t want my work to depict my emotions or control what others feel, but instead try to create experiences that feel boundless, free, open-hearted in an attempt to propel one to feel something. In this way, the paintings aren’t static. They allow for the work to transform with each person.

Memory is created through my physical process of painting as well. My paintings synthesize the energy of moments in time and evolve through stages. As the primed canvases are propped on the floor I pour, splatter, squeeze, spray, and flick diluted paint onto them. The poured grounds become energetic fields that develop slowly. The canvases develop from each surface layered daily with thin stains of paint—scumbling, glazing and sanding in between. There is a tension that arises between the immediacy of pouring and the timely process of adding and erasing. An order or pattern is created through the chaos. Rather than illustrating these contrasts, the paintings combine opposing forces. Once dry the entire painting is sanded down so that hidden layers reveal something unexpected. The memory of each color and mark activates the next. The paint becomes embedded and integral to the surface in a geological way. From building up the ground, to then excavating it repeatedly over time, the painting materializes like the formation of a crystal. Each day, I apply the remaining paint left on my palette onto the edges of the painting. This gesture acts as a record of my process.

Synesthesia is a big part of my work. I am a color-tactile synesthete. I feel physical sensations when I see color. It is largely how I process the world. A feeling of a place or sometimes even a sound, scent, or taste might evoke different colors unconsciously. I don’t necessarily recognize what I am trying to bring forth until a painting is done. I try to be as present with it and actively listen to the work as it tells me what it is. I trust the process.

I am also a Reiki healer and a long-time Vipassana meditation practitioner. This particular meditation practice is one that assists in cultivating a deep awareness of sensations in the body. I draw parallels between this form of mediation and my painting practice. When developing a painting rather than thinking about an image or something concrete, I think about sensations much like what one might feel. I consider how to depict parallel contrasting formal qualities that can coexist within a painting. For me, these subtle differences in texture, color, and surface mimic life and activate the energy in the work.

My paintings are experiential and reflect states of being. I consider them to be more like atmospheres than anything else because they shape-shift depending on what one brings to them. They capture the essence or feeling of a place or something familiar that words fail to describe accurately, much like dreaming or memory. Liminal spaces that exist between internal and external worlds are what interest me most.

Rema Ghuloum

Artist

Leila El Zabri: Your painting seamlessly weaves together the human and the natural, with women and a towering tree at its heart. In what ways do you see womanhood as rooted in the spiritual traditions of the Middle East? How does femininity influence your artistic expression?

Randa Maddah: For me, femininity is connected to the earth and to life. It’s an energy that moves between creation and transformation. Woman and nature are linked in this sense, both have the power to renew, to hold contradictions, and to create new life even from within loss.

In Sufi traditions of the Middle East, I also find this connection present. The woman appears as a bridge between the material and the spiritual, between what is seen and what is unseen, a being that lives between two worlds and expresses both. Just like nature, which is reborn from its own death and constantly renews itself.

This understanding of femininity as a force of creation and change is what nourishes my artistic work. I don’t see the body as a fixed image of womanhood, but as a space where spirit and matter move together, exploring the relationship between human and nature, between existence and transformation.

For me, painting is a form of meditation, a feeling that life is always capable of beginning again.

Leila El Zabri: How do you navigate the tension between fertility as a symbol of life and renewal, and the scars left by exile or erasure? Can a dream be fertile even when rooted in loss?

Randa Maddah: Loss and absence open up a space for imagination and reconstruction, and sometimes it is pain that drives life to begin anew. In this work, the body and nature are not separate elements, but a single body carrying the same memory and transforming through it. The body is an extension of both the earth and memory. Exile, for me, is not merely a distant place, but a condition experienced by the body when it is uprooted from its surroundings, as it tries to remember where it came from.

The earth in the painting is not a background but a being that bears the traces of absence as well as life. It embodies a kind of quiet resistance and a desire to remember, to persist, and to continuously transform.

The woman appears as a bridge between the material and the spiritual, between what is seen and what is unseen, a being that lives between two worlds and expresses both. Just like nature, which is reborn from its own death and constantly renews itself.

Randa Maddah

Artist

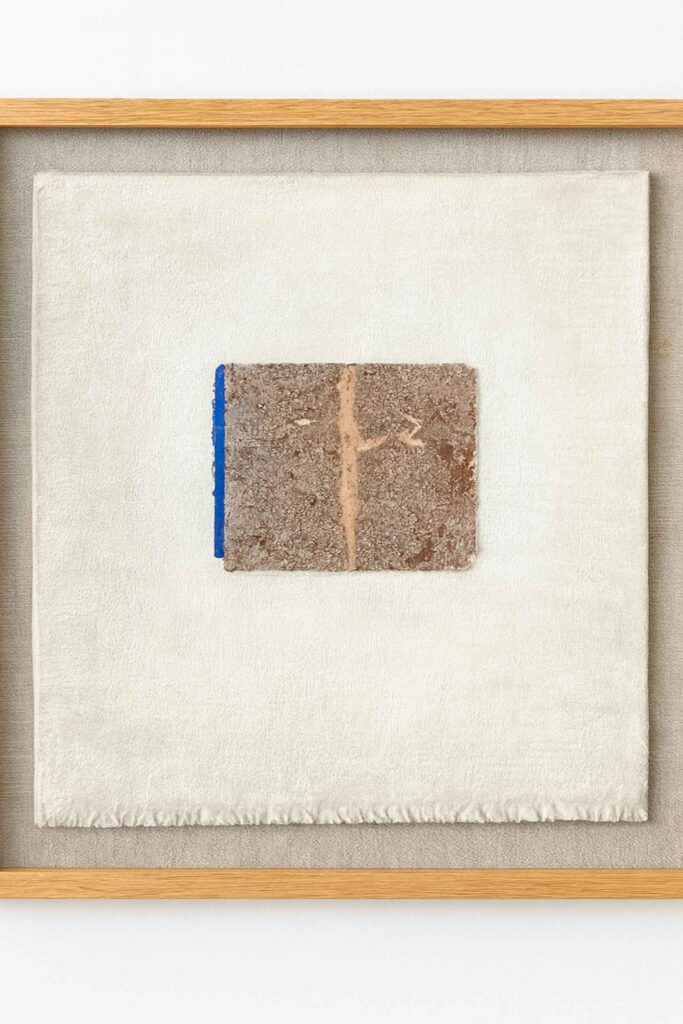

Leila El Zabri: Your work often engages with surfaces as sites of transformation, where traces, cracks, and pigments become a language of repair and erosion. How does the materiality of your work reflect the patterns of rupture and reconciliation embedded within the cultural memory of the Middle East?

Chafa Ghaddar: The material ruptures in my art evoke that something has happened. A disruption of a sort. And it’s beyond the event; materials consistently reflect a bold tension and clash yet a surrender into a quiet harmony or the possibility of reconciliation. They arrange themselves with a lot of stamina to hold space for Colors and compositions. Through this function, the materials require to be trusted, held and supported, inviting you to touch, even with your eyes, to sit with them, to investigate. They sit at the liminal stage between being vulnerable yet in a constant state of becoming, while being whole and contained. They interrogate time while surpassing the event or sometimes preceding it. They’re interested in time beyond the event. They imagine a nonlinear narration of the land, the body, the room, and the wall, therefore evoking a landscape that consistently desires to regenerate. They’re abundant and intricate and sophisticated with their multilayered nature. They demand care and curiosity, they render walls and everything architectural into bodily visceral states. They’re driven by poetry and sensibility to space, time and trace.

Not only does this reflect a cultural memory of our region, but it also sits with its deep historical and actual complexities, reminding us that in those tensions and vulnerabilities prevail abundance, growth and aliveness.

Leila El Zabri: Your work explores the interplay between identity and the natural world. In Fertile Dreams, how do you perceive nature as a mirror or extension of identity? How does your artistic practice navigate the boundaries between the physical self and the environment?

Alymamah Rashed: In Fertile Dreams, I’m painting my humane angels on sheets of fruit and vegetable paper — strawberries, pineapple, cucumber, onions, and carrots — each harvested from the land and transformed into a living canvas. These grounds become earthly Edens where the angels are born, preserved, and spiritualized. The act of painting on such organic surfaces allows the figures to inhabit a fertile terrain — one that carries both the fragility and abundance of the natural world. Their halos, rendered in gold pigment, honor their divine vulnerability that transcends the earthly while still being rooted within it.

Through this process, nature does not simply mirror identity — it becomes its continuation. The boundary between body and landscape dissolves; my figures emerge as extensions of the land itself, eternally preserved within its fertile skin.

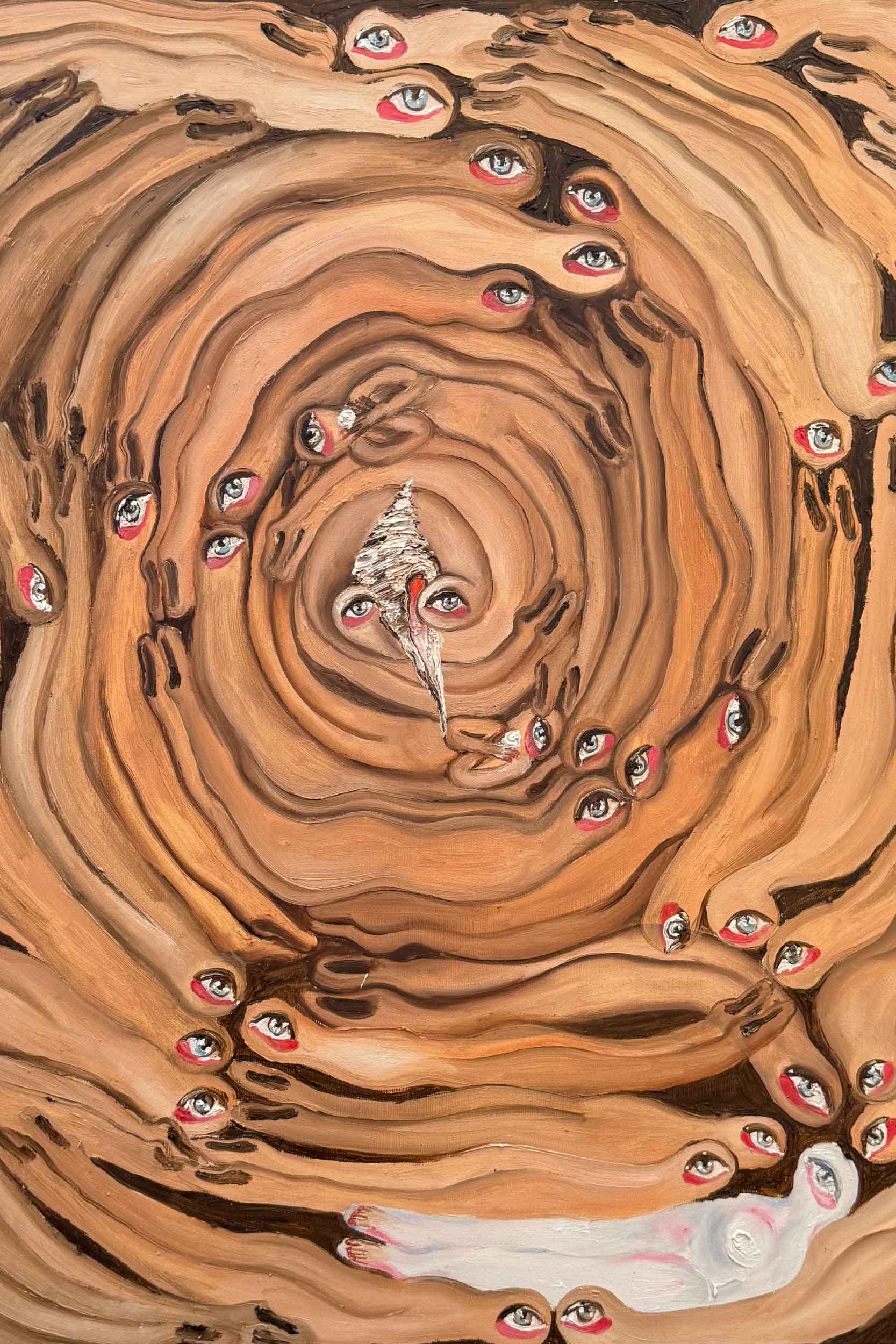

Leila El Zabri: Eyes appear as recurring symbols in your practice, often suspended between vulnerability and perception. What does the eye represent for you? Does it act as a portal, a witness, or something else entirely in your exploration of self?

Alymamah Rashed: The eye in my work is a window — a passage for the viewer to enter the narrative and float within the composition. It’s both a portal and a mirror, a space of perception where the self encounters its own reflection differently each time. Within Fertile Dreams, the eye becomes a journey of return — a spiritual threshold that invites the viewer to oscillate between seeing and being seen, between presence and transcendence. For me, it is not only a witness but a carrier of breath, a way of returning to the spirit through the act of looking.

The boundary between body and landscape dissolves; my figures emerge as extensions of the land itself, eternally preserved within its fertile skin.

Alymamah Rashed

Artist

Cover Artwork by Alymamah Rashed

Interview by Leila El Zabri

Leila El Zabri is Culture Editor at Planted Journal, through which she explores the overlap between natural, social and political realities. She is an Italian-Palestinian researcher focused on intersectional cultural dynamics, and her main interests lie in investigating the often unacknowledged social dynamics that accompany environmental crises. She is seeking ways to integrate human existence with nature.