I want my work to always come from a space that is reflective of Indigenous culture, Indigenous resistance, and a savage, stubborn, beautiful spirit that exists in Indigenous communities.

Demian DinéYazhi

Indigenous queer artist, writer and curator

Demian DinéYazhi´ is an Indigenous queer artist, writer and curator whose work confronts the entanglements of settler colonialism, institutional power, and survival while centring Indigenous, queer, trans, non-binary, and Two-Spirit perspectives.

Their work acts as a refusal and reclamation, making space for and affirming communities long marginalised and silenced and demanding accountability and transformation from institutions.

Humour, irony, and playfulness thread through their work, subverting oppressive systems and paying homage to those who have carried forward sacred knowledge and resistance.

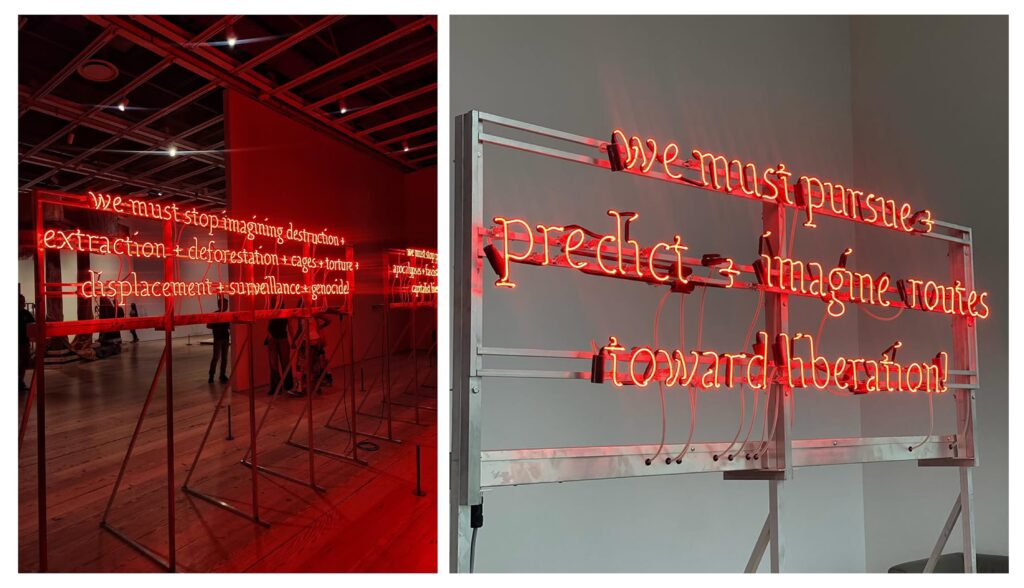

Anna Borrie: Your work in the Whitney Museum Biennial, “we must stop imagining apocalypse/genocide + we must imagine liberation,” addresses urgent themes of survival, futurity, and refusal. How does this work respond to, resist, or refuse the normalisation of that apocalyptic narrative in mainstream culture and institutions? Do you see this piece as a way of reclaiming the narrative?

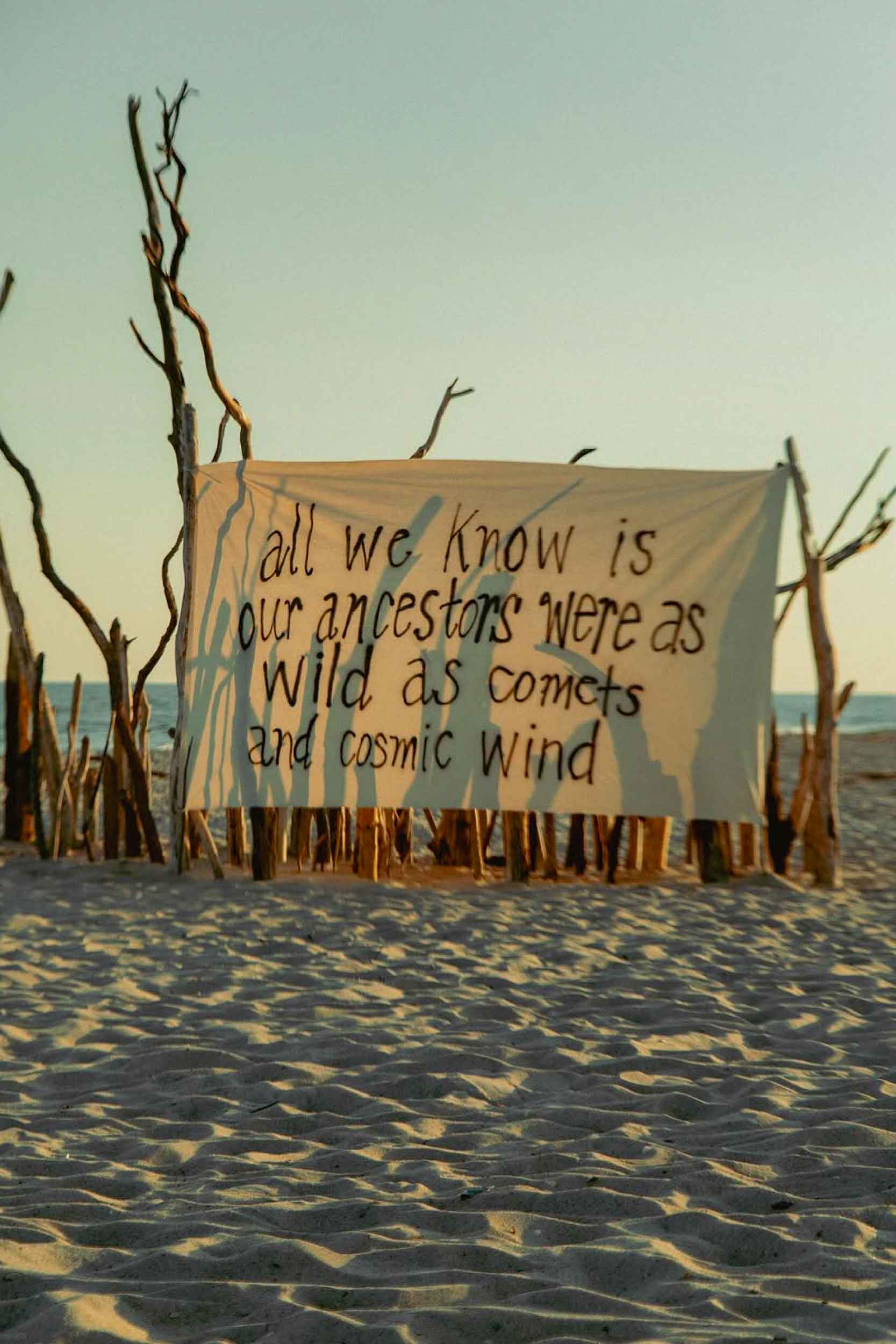

Demian DinéYazhi: The piece for the Whitney Biennial originated from some poetry sketches in 2019. I was in the headspace coming out of performing my second book, where I was thinking about what we leave behind: legacy. It is a colonial construct wanting to leave something behind but also an ancestral tradition. We hear the saying over and over again, especially when it’s tied to Indigenous sustainability of “nurturing communities with seven generations in mind”. I was thinking about what we are truly leaving behind or cultivating for future generations. So much of settler colonial culture is about consumption and exploitation and extraction; it contributes to narcissistic, volatile, post-apocalyptic terror. I think there is an obsessive addiction, which has ties to Euro-Christianity, about world-ending paranoia and surveillance. It is predominant in Western literature; like We, Brave New World, 1984, The Handmaid’s Tale.

As we witness people on social media, namely of colonial descent, showing up to demonstrations wearing The Handmaid’s Tale attire, we start to see these things being re-performed, but to what end? Is it actually a subversion of fascist settler colonial governments that are being challenged through subversive literature and theologies that are put forward by Western sci-fi? Who’s really subverting whom, and who’s really benefiting from these speculative warnings? Even though they were written through deep, legitimate concerns by writers who were genuinely furious and attempting to warn future generations. It leaves me wondering what could be possible if instead we focused on thinking and writing stories about building societies that were actually about replenishment, revolution and victory? The piece that was in the Biennial is an excerpt from a poem that preceded the pandemic from my third book of poetry, “WE LEFT THEM NOTHING”. As I started writing it, I was thinking about resource extraction and comparing settler colonial invasion and land grabs to Black Friday consumer hysteria. Then the pandemic happened and distressing things started to play out in front of us. People were going to grocery stores and hoarding resources from the shelves, completely paranoid about where we were headed as a country because of failed leadership. It was really hard to write that piece, to finish writing that book during that time, because some of the themes that I was confronting were actively playing out all around us.

I wanted that book to be about embracing the late 90s, Y2K nihilism, and themes of apocalypse through alternative media. Thankfully, a lot of social protests erupted through the writing of the book in 2020, and they reminded me that even though there’s extraction and exploitation and fascism, there is still hope. There is still such a remarkable amount of hope and learning and evolution that we’ve made as a society, also as politically minded, deprogrammed, anti-colonial revolutionaries.

So much of settler colonial culture is about consumption and exploitation and extraction; it contributes to this really narcissistic, dark, post-apocalyptic terror. It leaves me wondering what could be possible if instead we focused on thinking and writing stories about building societies that were actually about replenishment, revolution and victory?

Demian DinéYazhi

Indigenous queer artist, writer and curator

Anna Borrie: How can art bring alternative futures closer? Do you think this is ever fully possible within institutional exhibition contexts?

I think there is potential there, but we’re not hitting that potential right now as artists. A lot of that is reflected in the fact that a lot of artists who are taking up museum space and institutional space are artists that have access to an overwhelming amount of privileges and resources, while artists such as myself and other queer, trans, non-binary, Two-Spirit, and artists of colour and disabled artists are left fighting over rations.

During the pandemic, we saw a lot of non-represented artists making work that was revolutionary and that was pushing people forward. Those artists have had to reposition themselves or have left the arts in order to survive because they were outcast as the arts industrial complex shifted its priorities. We are witnessing that now as artists are censored and losing opportunities for speaking up about genocide, Palestine, ICE raids, and immigration rights. I’ve been censored many times.

Censorship is a validating signifier of our collective power through our art and poetry and agitation. However, it is also a cowardly move that attempts to suppress voices that, unfortunately, we see play out on a pretty regular basis. Institutions pride themselves on highlighting marginalised voices, but they’re not interested in actually addressing the issues that marginalised artists experience on a daily basis. They’re interested in our work to the extent that it generates funding or maintains their supremacy. If they were dedicated to the actual survival of artists, they would fund us more; they would help us figure out ways that we can exist outside of these structures that are interdependent on settler colonial galleries that exploit our work while suppressing issues that affect our survivability.

Within the last year alone there have been so many artists that have been silenced. So there is a demand for a systemic breakthrough but It takes a large art community to do that. It takes artists and institutions that have an absurd amount of privilege to disrupt their comforts that normalize hegemonic systems. It takes those artists speaking up and working from a place of integrity and discomfort to challenge the spaces that benefit their legacy.

This has been an ongoing narrative, and Palestine has helped us see that the intersections of colonial injustice are so deeply woven into who we are. We have been so brainwashed for so long. It sickens me that we’re this far into genocides and fascist conquests and so many refuse to speak in spaces that have harmed our communities for centuries.

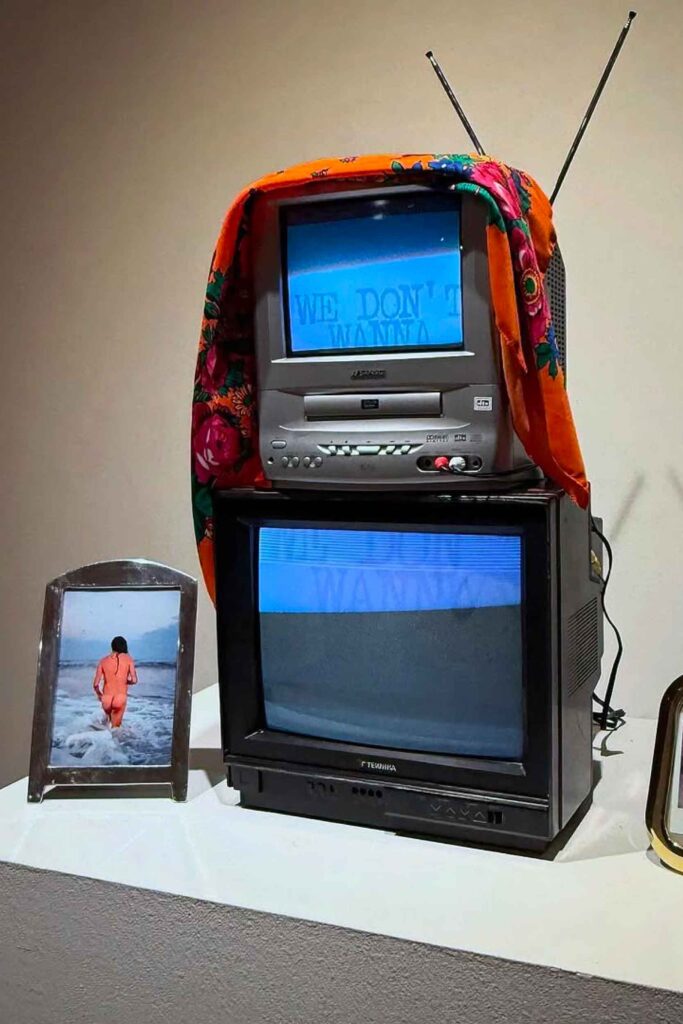

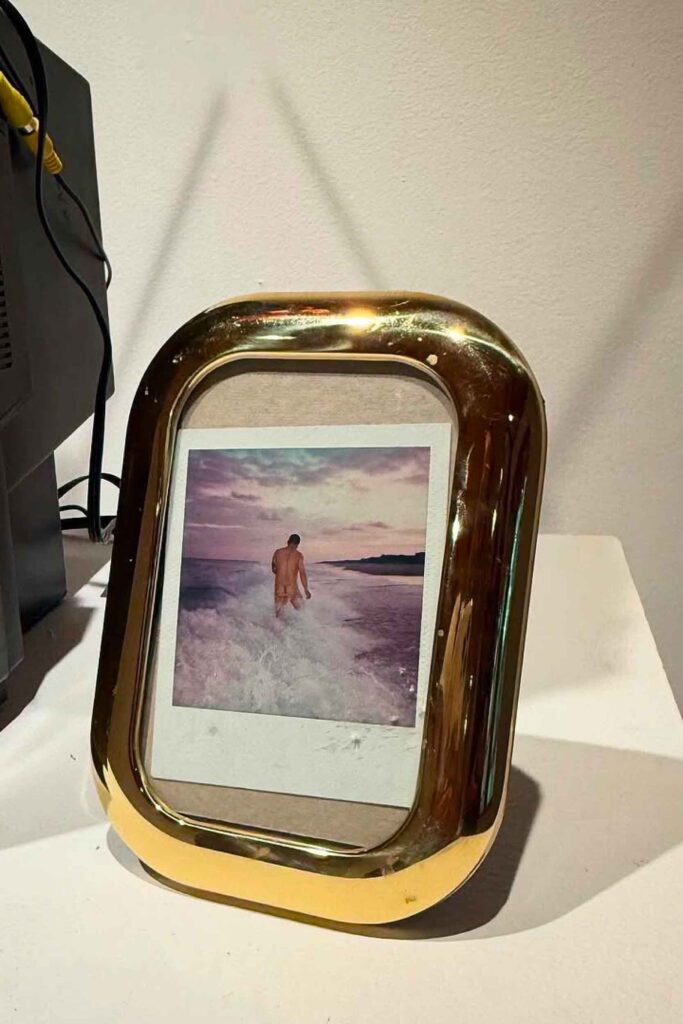

Anna Borrie: The weight of memory and accountability feels deeply present in your work. In the work “my ancestors will not let me forget this”, there’s also a sense of play, irony, and subversion. Do you see playfulness as a form of refusal, especially when engaging with systems that have historically tried to erase or suppress Indigenous and queer identities?

Definitely, it’s all a game at the end of the day within the arts; that’s how they want to operate. So we have to figure out ways to play, be players but not be “played” in these spaces. One of the amazing things is seeing who will fuck with it or who will jump on the other side and play Connect the Dots. There are moments when my work is actually pretty humorous; depending on the community, my work definitely hits a nerve and delivers a bit of a punch or a punchline. I’m always curious who’s going to support the work. When I started, I just wanted my work out there and to have my community represented in some form. Whether that was Tumblr, a small gallery, an artist-run gallery, or a DIY publication, showing in DIY spaces was an essential vehicle to show my work.

We are witnessing that now as artists are censored and losing opportunities for speaking up about genocide, Palestine, ICE raids, and immigration rights. I’ve been censored many times. Censorship is a validating signifier of our collective power through our art and poetry and agitation.

Demian DinéYazhi

Indigenous queer artist, writer and curator

Anna Borrie: In a moment of escalating political violence against trans and queer people, do you see your work as a form of witness, or perhaps a call toward a different way of being in community?

Demian DinéYazhi: I think it’s another way to show up for the community. I respond to the ways that I’ve been exploited by institutional spaces through my unique history and experiences with institutions and their bureaucratic processes. It’s funny; when I was first asked to show work in the Whitney, I knew very little about that institution.

After my experience I would see problematic things come up from the Whitney or other institutions that I worked with. It felt very risky speaking out, as though my gratitude for the miniscule pay cheque and momentary exposure should keep me in line. But oftentimes, there is no follow-up about our careers or long-term commitment.

When the land acknowledgements came out, it became more evident. I was really nervous when the Whitney Biennial curators invited me to do a studio visit and then invited me to participate. At the time I was going through some censorship in Oregon for a banner that I had produced in 2020 in response to George Floyd’s murder and the Black Lives Matter uprising. So I was really conflicted about whether or not to participate. I’m super critical of these spaces; I don’t think they’re doing enough for artists. But I had really affirming conversations with Chrissy and Meg from the Whitney, who were really supportive. I felt heard; they were receptive, they were curious, and they assured me that my voice would be validated and championed.

So I gathered up all my uncertainty and saw that it was an opportunity for me to show up for my own community in response to ongoing political tensions in the world, but also because Indigenous, queer, trans, non-binary and Two Spirit artists are largely under-represented in these spaces.

Political messages have become increasingly excluded in these spaces. So my decision to work in spaces requires constant negotiation; I have to remind myself that, to some degree, if my voice wasn’t there, then there wouldn’t be an Indigenous, non-binary, trans, queer person unsettling that space.

It’s also a dangerous space, because we know these spaces have contentious connections; there’s dark money and dark power attached to institutional spaces and arts funding. It can be terrifying; you shouldn’t have to feel unsafe being an artist working in these spaces. Since these spaces are based on settler colonial logic and foundations, they’re going to be dangerous. They’re going to be unsafe and threatening; they have ulterior motives.

Anna Borrie: You’ve spoken about how your heritage deeply shapes your perspective on the world. How can art serve as a bridge between Native and non-Native communities, especially when it comes to building understanding and challenging misconceptions within the US?

Demian DinéYazhi: They can build bridges if there are artists and people from marginalised communities in these positions of power and influence. Not just one or two token representatives who’re given positions that maintain these systems yet are unable to deliver because the rest of the structure is still corrupt. These spaces can change but they need to be entirely transformed in order for that to happen. Which means a lot of people in power need to step down and the system needs to be restructured, because it’s a broken, corrupt system. People act like there’s no other way, but at one point these systems didn’t exist. It just takes dedication, patience and time.

Political messages have become increasingly excluded in these spaces. So my decision to work in spaces requires constant negotiation; I have to remind myself that, to some degree, if my voice wasn’t there, then there wouldn’t be an Indigenous, non-binary, trans, queer person unsettling that space.

Demian DinéYazhi

Indigenous queer artist, writer and curator

Anna Borrie: Prints historically have been tools of agitation, mass communication, and collective resistance. How do you see your printmaking work participating in a lineage of refusal?

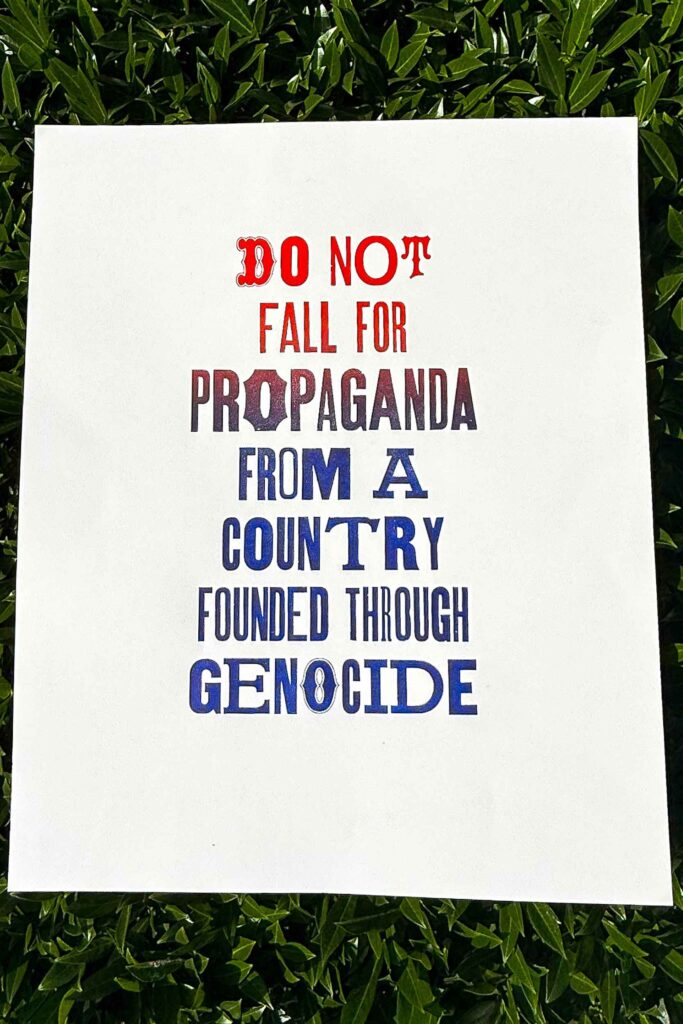

Demian DinéYazhi: For me, printmaking is rooted in activism. I see them as political posters and banners. The project that I’ve been working on with Mullowney printing in Portland, Oregon, came out of the discomfort of the Whitney Biennial. It also came out from a series that I’ve been working on called “extractive industries”, which is rooted in the ancestral, Indigenous tradition of institutional critique. My work aims to create awareness of the toxic environments and practices that exist within the arts industrial complex.

The series “PROTECT THE SACRED VOICE” is about creating statements that respond to the political tension of this time. It’s about maintaining the power of the artist’s voice and continuing to nurture it, respond to it, and build community alongside it. This more recent poster series is a way to continue the conversation and dialogue of empowerment with my community. I think of letterpress printmaking, publishing these posters, as an ongoing call and response with the community. I want others to respond to them, think about them and feel motivated in the sense that they begin to unpack some of the injustices that exist within their own communities. I’m always curious how that helps motivate others to continue creating and defying censorship or self-criticism.

Anna Borrie: Reverence is the deep respect and acknowledgement of the interconnectedness of all beings, recognising the value and significance of every story, culture, and experience. Do you consider your work a reflection of reverence for these connections, and how does that shape the stories you tell through your work?

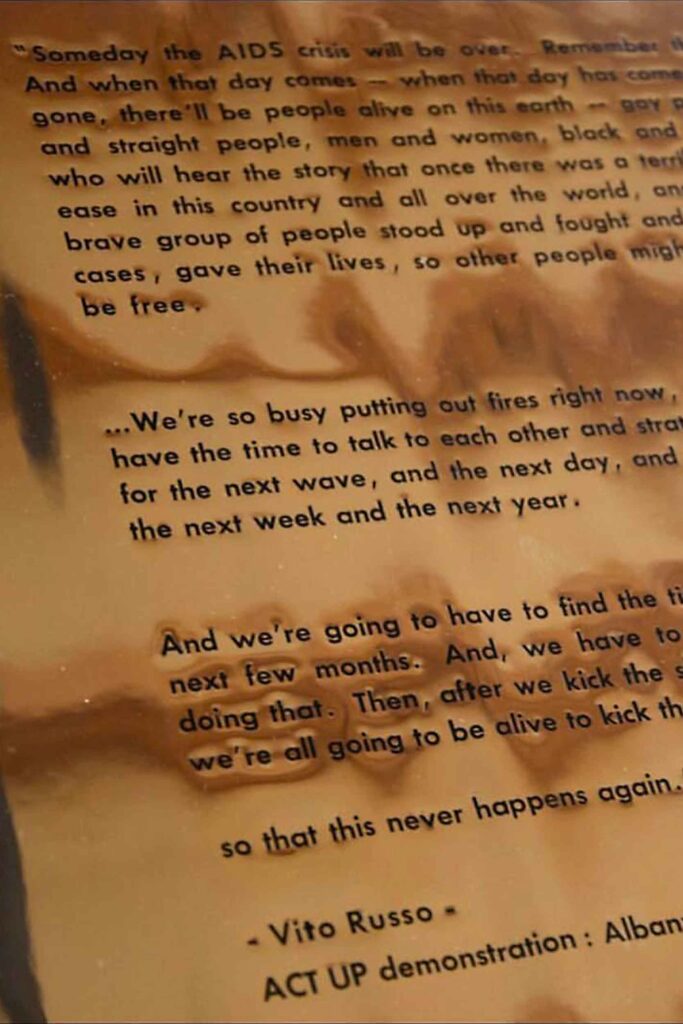

Demian DinéYazhi: Some of my first letterpress prints were homages to people who inspired my practice. On reflective gold dura paper I printed Vito Russo’s speech called “Why We Fight”, which is a gut-wrenching speech that he gave during the AIDS crisis, which is ongoing, as this administration and RFK Jr will remind us.

Some of my earliest work came from a deep respect for those who came before me, for those who held the torch at one point and who maintained sacred ground: HIV/AIDS, trans and queer activists. Also my grandparents, parents, siblings, relatives, my culture, and Indigenous communities. The first neon sign that I created is based off of the Indigenous Diné ceremony, because I wanted my work in that medium to always come from a space that was reflective of Indigenous spirituality, Indigenous resistance, and a savage, stubborn, beautiful spirit that is cultivated in Indigenous communities. I don’t see that ever going away; I’m always trying to pay some sort of homage to others in my community and others who have helped to shape this world, and also those who died resisting colonialism so we might have a fighting chance. The piece in the Whitney is dedicated to the late activist Klee Benally who helped shape me in so many ways. Especially in thinking about the ways that we conduct ourselves in settler colonial institutions, and to continually demand more from ourselves as we’re also demanding more from these institutional spaces. Reverence is one of the key traditional rituals that is foundational to my work.

I’m always trying to pay some sort of homage to others in my community and others who have helped to shape this world, and also those who died resisting colonialism so we might have a fighting chance.

Demian DinéYazhi

Indigenous queer artist, writer and curator