Love Canal: Evidence of Injury | Shanna Merola

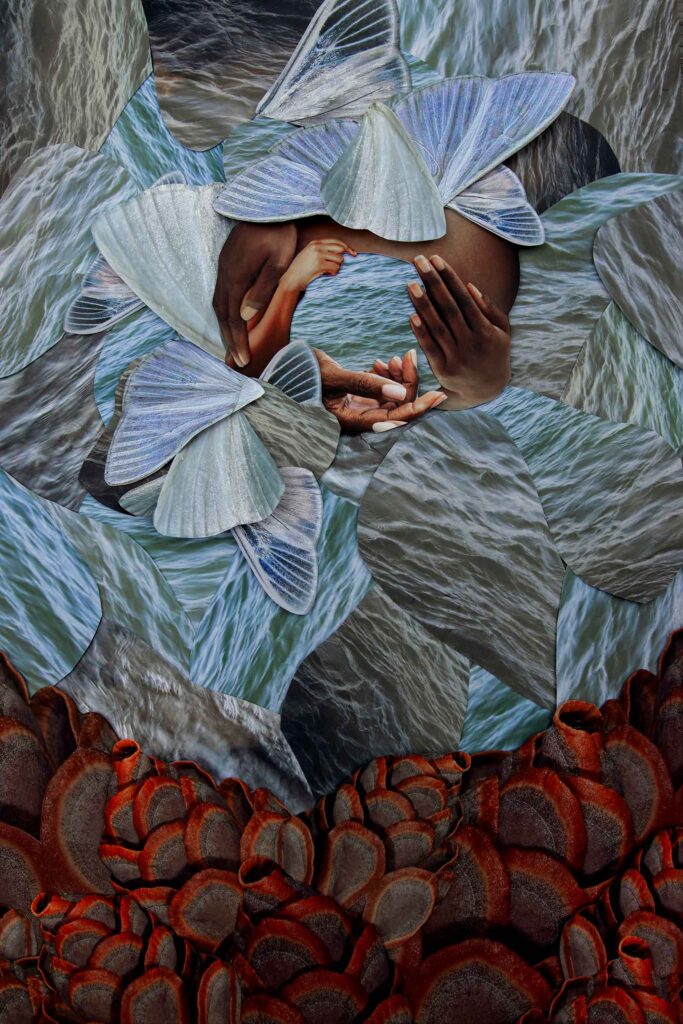

Dioxin, cadmium, arsenic, lead… what happens over time when the human body is exposed to these elements, and what happens to the land?

In the late 1970s, toxic waste sites like Love Canal and Valley of the Drums became household names when major court battles for environmental protections dominated the national media. Although it’s been decades since these stories emerged, grassroots organizing during this time led to sweeping federal legislation that continues to impact our lives on a daily basis. In 1980, due to intense media scrutiny and public pressure, congress established the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act. CERCLA (otherwise known as the Superfund program) authorizes the Environmental Protection Agency to clean up contaminated sites while holding corporations financially responsible for unregulated dumping of toxic waste.

“Love Canal; Evidence of Injury” examines the industrial legacy of North America’s first Superfund site through the unsung history of women who organized for environmental justice in their neighborhoods.

Nestled just outside of Niagara Falls this predominantly working-class town became headline news when leaking dioxin containers were discovered buried just beneath the asphalt. According to the EPA, a chemical company that produced insect repellant, soap, perfume, and cosmetics used this land in the 1940s and 50s to dispose of over 21,000 tons of hazardous waste. Over time, these dangerous substances became a toxic stew, contaminating the water, soil, and grounds of an elementary school as well as nearby properties. By the late 1970s the mothers of Love Canal were reporting extremely high rates of birth defects, miscarriages, and childhood leukemia. Canvassing door to door throughout the neighborhoods they conducted their own scientific research, documenting illnesses in each home and making connections to the strange substances that surfaced whenever it rained. With no help from city officials who publicly denied these reports they began archiving, documenting, and writing to congress – only to have their work dismissed as “useless housewife data”.

Today, wildlife like milkweed and mullein thrive despite elevated toxicity levels that remain ever-present within the landscape.

Driveways to nowhere, broken streetlights, and decommissioned fire hydrants mark the empty streets adjacent to a fenced off piece of land where the 99th Street School used to sit. Empty lots where houses once sat crumble as feral gardens of lupine and Queen Anne’s lace volunteer to remediate the soil. But, in and around the containment zone, are the stories of mothers who fought for the right to a safe and healthy environment. The intersections of race, class, gender, and housing are inextricably linked to the struggle as well, though many of these stories were omitted from the mainstream narrative. Broader themes in the series explore adaptation, toxicity, reproduction, mutation, and survival – with a focus on the interconnectedness of our fragile ecosystem and the human body.

In every state across North America there are versions of Love Canal to varying degrees– industrialized areas where the surrounding land and people have been deemed less valuable than corporate profit. From “Cancer Alley” outside of New Orleans, to Hunters Point, California the legacy of toxic industries seems inescapable. In this sense, the story of Love Canal is not unique; however, it once played a pivotal role in raising public awareness around corporate accountability. And – unfortunately – this story is still unfolding to this day. Although entire streets were permanently bulldozed around the containment zone in the early 1980’s, those immediately north and west were refurbished instead, following a 200-million-dollar clean-up which attempted to cap the toxic waste. In the 1990s, upwards of 200 houses were given new roofs, windows, and vinyl siding and deemed suitable for rehabilitation. The neighborhood was renamed Black Creek Village, with houses for sale at twenty percent below market value. However, several lawsuits have been filed by current residents who claim to be getting sick once again – nearly fifty years later – from the mysterious chemicals welling up in their basements.

Words and Artworks by Shanna Merola

Shanna Merola is a visual artist, photographer, and legal worker. Her sculptural photo collages are informed by the stories of environmental justice struggles past and present. Travelling to EPA designated Superfund sites, she has documented the slow violence of deregulation – from her own neighborhood on the Eastside of Detroit to Chicago’s Altgeld Gardens and Love Canal, NY. In addition to her studio practice, she has ten years of experience working in civil rights law through the National Lawyers Guild Detroit and San Francisco Chapters.